Rural employers should offer paid time off to employees who are getting vaccinated against COVID-19. Vaccine information needs to be offered from trusted sources, and opportunities to get the vaccine need to be omnipresent.

Those were among the recommendations of experts at an online event Thursday that brought together government, business and community leaders specializing in the needs of rural communities. The National Rural Business Summit event included discussion of the barriers people in rural communities face to getting vaccinated, the range of attitudes toward vaccines and the best ways business and political leaders can address people’s concerns.

Rural areas have lagged behind cities and suburbs when it comes to vaccinations. That’s in part because, as numerous public opinion polls have shown, vaccine hesitancy is highest in rural areas. In Wisconsin, the counties with the lowest proportion of residents vaccinated are sparsely populated Clark, Taylor and Rusk counties.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

But there are also structural factors that are keeping some rural residents from getting their shots, panelists said.

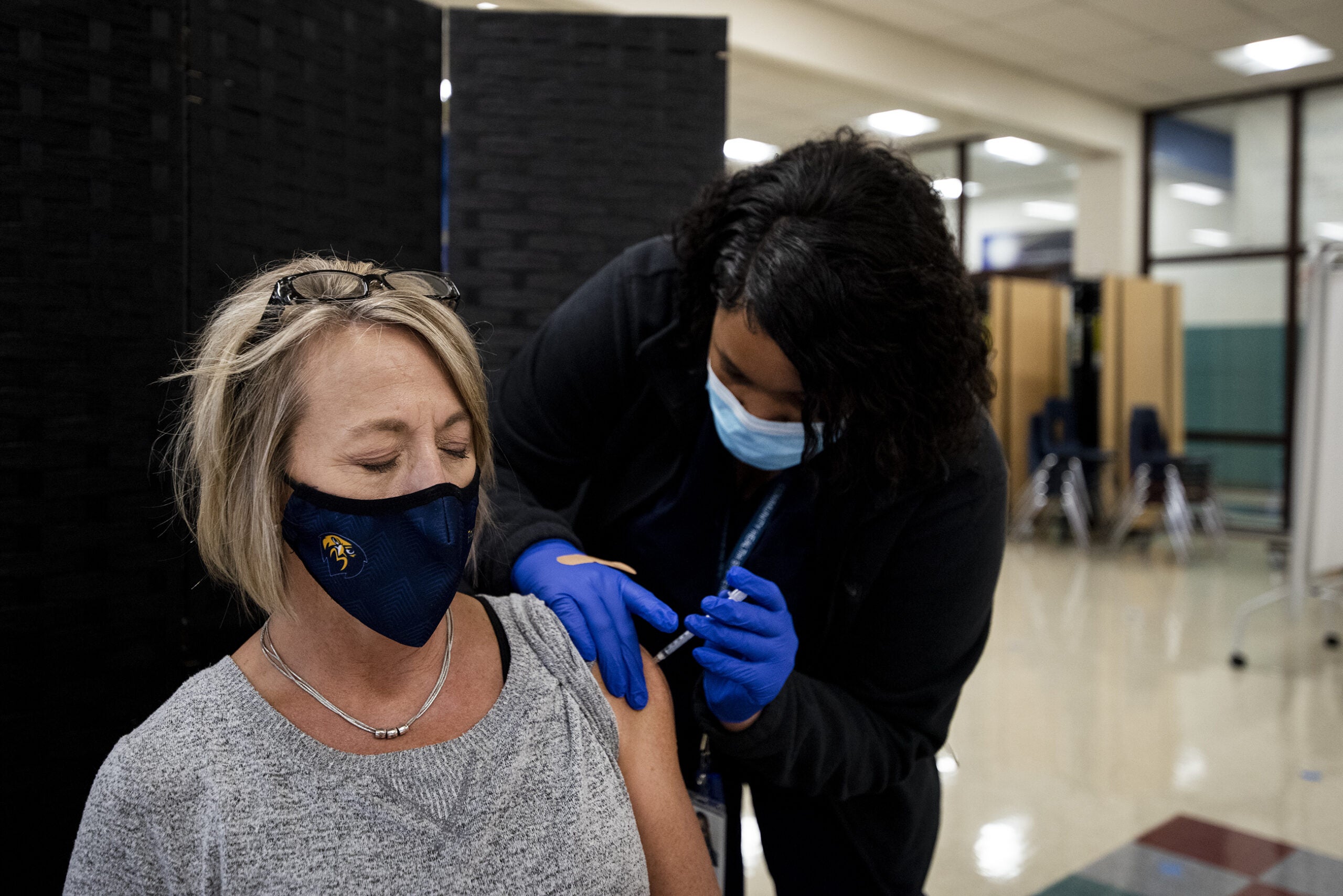

“Not always in small towns are you going to have the opportunity to leave at lunch to go to the local hospital to get vaccinated and come back,” said Alan Morgan, CEO of the National Rural Health Association. “For a lot of these communities that have lost hospitals, lost health clinics over the past year or haven’t had them, it’s going to necessitate driving half an hour, an hour, an hour and a half” if mobile or employer-based clinics aren’t available.

“It comes down (to) us as business leaders to talk to our employees,” Morgan said. “‘Have you gotten vaccinated? Do you have transportation to get vaccinated? And can I give you a couple hours off so you get that and keep our business safe?’”

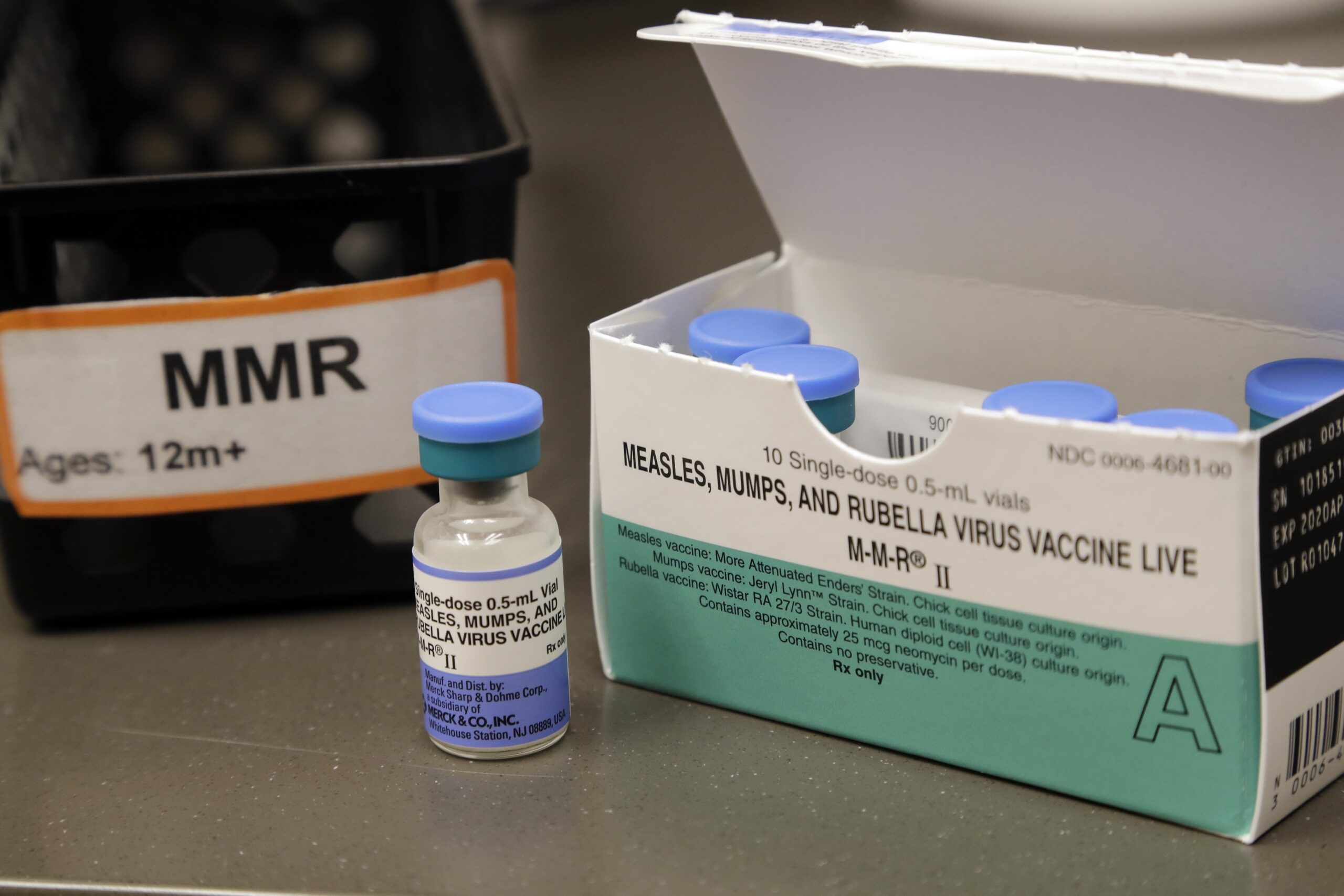

Vaccines protect individuals from infection, but they also have been shown to dramatically slow the spread of COVID-19, which protects both those who’ve been vaccinated and those, including children younger than 12, who can’t be yet.

President Joe Biden has called June a “month of action” on vaccines and is offering incentives including free beer and sports tickets to try to encourage more people to get theirs. At Thursday’s event, White House vaccinations coordinator Dr. Bechara Choucair said people this month will see “vaccines in barbershops, baseball games (and) NASCAR races,” and that the administration would be leading canvassing and phone-banking efforts focused on areas with low vaccination rates, including rural areas.

One thing experts say doesn’t work to reach vaccine-hesitant populations is threats. In public opinion polling presented at the summit, people who said they’re unsure whether or not to get vaccinated said their biggest fear is that they’ll be forced to get one whether they want to or not. But employers such as the Minnesota-based Land O’Lakes, which has multiple plants in Wisconsin, said they’ve seen success reaching their employees by making information and on-site vaccinations available and by offering workers time off.

“We are offering not just the mass vaccination clinics but also walk-ins at certain locations, and we’re continuing to see that steady drumbeat of requests for vaccine,” said Tina May, the company’s vice president of rural services.

U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said the Biden administration is seeking a balance in its rural outreach efforts.

“We recognize and appreciate at USDA that there are multiple reasons why folks may be reluctant to be vaccinated, and that has to be acknowledged and that has to be respected,” Vilsack said. “But I think it is important for us to do what we can to educate individuals, to remind them of the responsibility they have to themselves, to their family, to their community and to their country. People out in rural America have a particular connection to family and community and country, and I think each of those — the family, the community and the country — benefit when more of us get vaccinated.”

Recent Polling Shows Opinion Shifts Toward Vaccination, Including In Rural Areas

There are also signs in public opinion polling that COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy has declined considerably in the last six months. There is still a segment of the population who is strongly opposed to getting vaccinated, but it’s a distinct minority compared to those who say they have already gotten their shots or are open to it.

Rural communities have a higher proportion of people who say they will “definitely not” get vaccinated. In May, polling by the Kaiser Family Foundation found this described 15 percent of all respondents nationally, but 24 percent of rural residents.

But Mollyann Brodie, executive director of Kaiser’s polling division, said there is evidence that many people who once had questions about the vaccine have gotten satisfactory answers.

In December, 39 percent of all respondents and 38 percent of rural residents said they would “wait and see” whether to get vaccinated. As vaccinations have become more widespread — about 51 percent of Americans have now received at least one dose — that number shrunk in May to just 12 percent among all respondents and 11 percent of rural residents.

Brodie said those data suggest that the national campaign has succeeded in persuading some people in the “movable middle” that COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective. And notably, that group makes up the same proportion of people in both rural and non-rural areas.

“Rural communities have the exact same opportunities as other communities in the nation,” Brodie said. Depending on measurements, she said, there are 12 to 15 percent of people who are “interested in the vaccine, they have questions about the vaccine, but they’re ready and they’re willing to think about making the choice for them and their families.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.