Wisconsin’s school funding structure is like a layer cake, with layers changing in size, shape and flavor from top to bottom.

Under the current structure with revenue limits and funds based on enrollment, school districts find themselves with increasing regularity placing ballot questions before voters as the only way to fund everything from new construction to operational costs, such as employee compensation.

Since 2015, voters in various Brown County municipalities have approved school districts requests for roughly a combined $225 million extending out far as 10 years at a time, over state-imposed revenue limits, and taking on $264 million in debt with referendums.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Brown County isn’t alone either.

To understand the reasons why school referendums have frequented ballots, this article includes a primer on the funding structure and what leads school districts to go to referendums.

Ari Brown, researcher at the Wisconsin Policy Forum, said schools in Wisconsin are funded from three main sources, state, federal and local monies.

He said local revenues come from property taxes, which total billions of dollars a year in Wisconsin.

Prior to 1993, Brown said local school districts generally had the authority to raise as much as they deemed necessary and go to the local taxpayers to cover it, with the state covering a certain percentage.

In 1993, he said the Wisconsin Legislature imposed revenue limits as a way to control local property taxes.

Brown said the state-established limits were set based on each district’s revenues in the prior year, and now affects the amount a district can tax each year.

As the years have passed, he said these limits have increased, but a district can still be hampered by what it was spending prior to the limits being established.

A district’s revenue limit is the maximum amount of revenue that may be raised through general state aid and property tax for the general, non-referendum debt and capital expansion funds, also referred to as Fund 10, 38 and 41.

The revenue limit is determined by the full-time equivalent of resident students, averaged over three years, multiplied by the district’s maximum revenue per student.

Property value is factored into the school aid formula for specific districts.

State aid, in part, factors in the resident student count and a district’s property value, with fewer students and higher property values bringing in less state aid.

As a result, state aid could decrease as property values increase or student enrollment decreases.

Brown said lawmakers decide how much to adjust the state aid portion of the per-pupil revenue limit, if at all.

“Let’s say you are a district that has a low per-pupil revenue limit, depending on how your property valuation changes, and all of the other things that go into the (state aid) formula, things are happening both in regards to how much you’re getting from the state and how much you can increase property taxes,” he said.

General, or equalization aid, is the largest form of state aid, Brown said.

Equalization aid is based in part on the relative fiscal capacity of each school district as measured by the district’s per-pupil value of taxable property.

Adding another layer to the cake, categorical aids can only be used for certain things, based on student characteristics, and those aids do not affect the revenue limit formula, he said.

Two forms of categorical aid help districts fund transportation and special education if districts meet certain requirements.

Brown said federal aid to Wisconsin schools is only about 7 percent of school funding, and primarily assists with certain programs like English as a second language, special education, high-poverty schools and others.

Nearly all funding not provided by the state or federal government comes from property taxes, and districts with less general aid (i.e., higher property values) rely more on property taxes.

Places like Gibraltar in Door County use property taxes more to pay for schools, because the district is considered “property rich,” (83.8 percent of its operating budget in 2020).

Places like Beloit rely more on state aid, because property taxes cover a smaller percentage (2.5 percent of its operating budget in 2020).

Both districts, however, receive up to their state-imposed, per-pupil revenue limit which comes from a combination of property tax revenue and general aid.

Brown said state-imposed revenue caps can affect the local property tax levy, so when general aid is cut, taxes tend to rise.

This means when lawmakers change state aid, they can also indirectly affect local tax levies, he said.

Lawmakers can affect local tax levies by either allowing for more or less general aid, or changing the increases in revenue caps.

“From 2001-02 to 2010-11, we had per-pupil average statewide adjustments between $200 and $300 increases every year,” Brown said of revenue limits. “Whatever the cap is, it’s rising. At some point it was tagged to inflation, which was a pretty standard thing. At times, it just happened at $200. But since that 2010-11 school year, one year there was a decrease, four of the years there was no increase, three of the years there was an increase less than $100 and the last two years there was an increase of $175 and $179.”

The Only Way Forward

Referendums allow districts the ability to exceed the state-imposed revenue cap, but only if voters approve them.

“Referenda can come in and be this bridge between what the state has allowed the district to garner in revenue and what they might actually need or feel what they need to be operating successfully,” Brown said.

Brown said there are two things referendums can be used for.

Operational referendums are used to add to a district’s operations budget for items such as increasing staff pay, adding more staff, or adding to the maintenance budget.

Operational referendums include a specific amount added on top of the state-imposed revenue limit.

He said capital referendums are used for building projects, such as major remodels or new buildings.

There are two types of operational referendums questions in Wisconsin: a recurring question, which would allow for districts to exceed the revenue cap in perpetuity and a non-recurring question, which is for a set period of time and requires future approval from voters to continue.

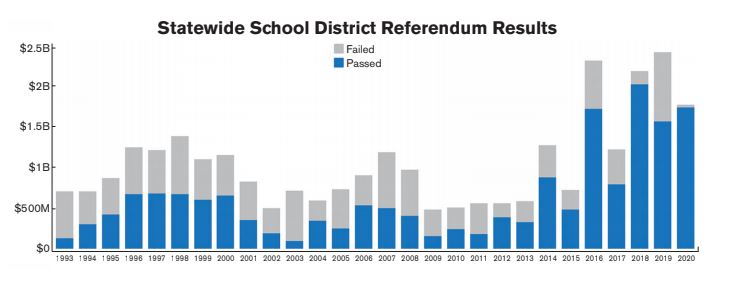

Brown said capital referendum questions authorizing debt are the most popular in Wisconsin.

With capital referendums, districts have discretion as to how much they want to levy in a given year to pay off debt.

He said the rise of referendums in the past decade coincides with the stagnant per-pupil rate increases of the state-imposed revenue cap.

However, Brown said the two aren’t necessarily tied together.

“It’s something you could definitely bring into the picture,” he said. “It’s hard to say correlation vs. causation there, but those are two things certainly happening at the same time, striking and in contrast to what was going on in the previous 10 years.”

Baking A Cake

Dale Knapp, director of Forward Analytics, the research arm for the Wisconsin Counties Association, compared the school funding formula to a layer cake poorly constructed.

“This is one of the things that bothered me for years and years and years, is you can’t explain (the formula) easily, because when they created it, they didn’t tie it together like they should have,” Knapp said.

He said the top layer on the cake is the revenue limits, but below that is enrollment, which determines those revenue limits.

Knapp said general aid and property taxes all interplay at the next layer to determine funding, but categorical aids also need to be included in the recipe.

“The easy way to explain this is, a district’s revenue is tied to enrollment,” he said. “When your enrollment declines, the revenue limits begin to tighten, and they don’t necessarily mean declining revenue. But initially, your revenue growth slows, and if it continues to decline, ultimately you can see your actual revenue decline.”

Knapp said this brings in an old argument from the public: if you are teaching fewer students, it should cost less money.

“The challenges for school districts is they have a lot of what I would call semi-fixed costs, for example teachers,” he said. “Suppose your average class size is 25, and you’re a medium-sized district, but you lose 50 students in a year. It’s going to be across multiple grades, so you can’t necessarily in that year lay off two teachers because you have 50 fewer students. You’re moving things around and you’re doing it over several years. So your costs don’t decline linearly with enrollment.”

Open Enrollment

Another layer to the cake could be open enrollment and resident enrollment, which breaks down funding differently for affected schools.

Open enrollment is the largest parental choice program in Wisconsin with about 60,000 participants, said Dan Rossmiller, Wisconsin School Board Association director of government relations.

Since the 1998-99 school year, under provisions of Wisconsin 1997 Act 27, parents and students are able to choose which public school district they would like to attend, if there are spaces available, Rossmiller said.

Locally, Green Bay and Ashwaubenon generally have openings each year, three other districts, De Pere, West De Pere and Howard-Suamico, have less and less availability and some stopped accepting general education open enrollment students nearly completely.

This is partially because of increased interest in open enrollment decreases the amount of available spots, as well as population growth in suburban districts, Rossmiller said.

Full-time open enrollment is used by the districts that take in students to receive additional revenue that comes from other districts where those students live and not the district’s property tax levy, he said.

The original district (the one where the student resides) still gets to count the student as part of its enrollment formula, but then sends a partial payment for each student to the district they open-enrolled in.

Rossmiller said the amount transferred is around $8,125, per student a year, which is less than the per-pupil revenue limit allocation the pupil’s resident district would receive for that student, although per pupil revenue limit allocation varies from district to district.

“What’s important to understand is that each district has its own unique revenue limit, and every district has its own unique dollar amount per pupil,” he said. “This all goes back to the 93-94 school year when the revenue limits were imposed, and it has to do with the existing per-pupil spending level of the district at that time. To change that relationship to the past, a district must seek voter approval to raise its revenue limit at a referendum.”

At the same time, as districts strive to prepare students for jobs that don’t exist yet, student enrollment numbers across Wisconsin have been trending down slowly for years.

“What’s happened since about the early 2000s is that enrollment has been decreasing,” Rossmiller said. “That’s what’s pinching school district budgets. As enrollment goes down, the state-imposed revenue limit reduces the revenue available to the district. The real problem in explaining this to the public is that every district has a unique situation and a unique explanation.”

With decreased enrollments making limited state and local funding harder to come by, and classrooms changing in the way of course offerings, technology and student needs, school districts seeking to keep pace with these changes and avoid having their students open enroll to neighboring districts may only have one place to go for relief – to the ballot for a referendum.

This story is product of the Northeast Wisconsin News Lab (NEW News Lab), a new collaborative effort providing technology support, capacity building and additional funding to boost local journalism and newsrooms. It includes six news organizations: Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Watch, FoxValley365, The Post-Crescent, Green Bay Press-Gazette and The Press Times. The University of Wisconsin-Green Bay’s Journalism Department is an educational partner, and Microsoft has provided financial support to the community foundation.