The blues, unique among today’s popular forms of music, is replete with truth-bending tall tales and publicity-seeking legends about its most famous practitioners. Whether it was P.T. Barnum-esque royal titles sprawled on gig posters or whispered deals struck at the crossroads, most stories involving the blues should always be taken with a pinch of salt.

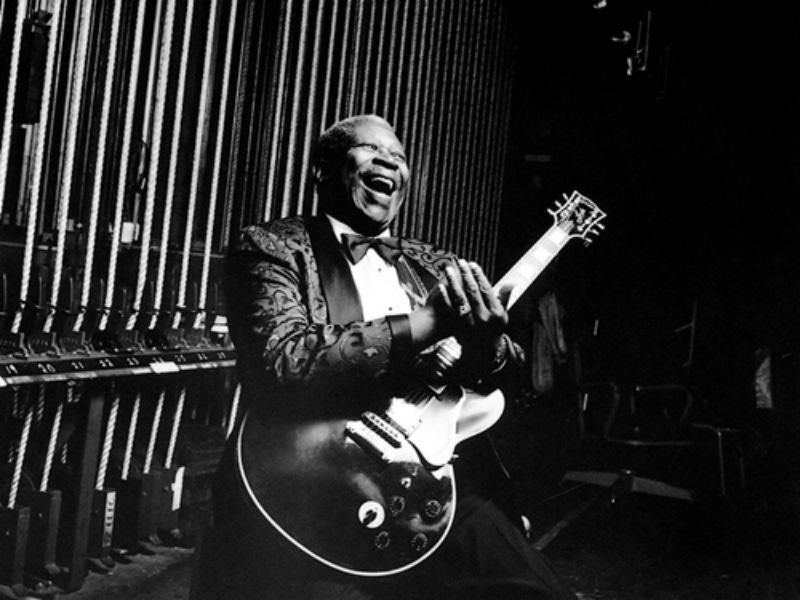

And so, hailed in his lifetime as “the king of the blues,” B.B. King had a lot to live up to. Thankfully, this was one legend who truly lived up to the billing. Mythology aside, King stood as a rotund musical colossus of the modern era. He was an essential evangelist for both the blues’ key musical norms and popularizer of its sonic values. Through both his roaring vocals and spare, stately guitar playing, King perfectly embodied the music’s core emotionality. And over the course of seven decades on the road, he became the blues most important road-worn ambassador.

King died on Thursday in Las Vegas after months of ailments reportedly connected to Type 2 diabetes. He was 89 years old.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Putting it plainly, King’s importance to the blues, and to Western popular music as a whole, can’t be overstated. His melodic music, which consciously skewed strict traditionalism for popular accessibility, offered an easy on-ramp friendly to enthusiasts and casual listeners alike. He also mastered a unique, economic guitar style that perfectly mirrored his bell-like singing. His single-string licks and solos served as a distinct model for subsequent players like Eric Clapton, Jim Hendrix, Robert Cray, Mike Bloomfield and Steve Cropper, among others.

King’s success began with serendipity. In one of those rare instances of being in the right person at the right time, King was the ideal proponent of the blues just when the music needed someone of his skillset to champion it. Most of the music’s founding generation were dead by the time the blues began to enter a popular renaissance in the 1950s and ’60s. Of those early players, such as Robert Johnson, Charley Patton and Blind Lemon Jefferson, only Son House and Bukka White were still alive and able to capitalize on the renewed interest.

As such, it fell chiefly to slightly younger musicians — Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and King — to become the blues’ great heralds and provide real-world inspirations for many of today’s blues acolytes and classic-rock stars. With Waters and Wolf in their graves only a decade or so after being rediscovered by the Rolling Stones and the like, King was the one of the few bluesman that fans could touch — both through the approachability of his music and his relentless touring schedule.

With hit songs like “The Thrill Is Gone,” “Sweet Sixteen,” “How Blue Can You Get,” “Every Day I Have The Blues” and “Nobody Loves Me But My Mother,” as well as his best record, the 1965 live album, “Live at the Regal,” King established his preeminence among his rivals and status of keeper of the flame.

Through his recordings and live performances, King’s music was seen as an embodiment of modern Memphis blues, but his music drew from a surprising variety of the blues’ variants like Texas and Chicago electric blues and particularly, jump blues, as well as older influences like ragtime and contemporary sounds like big-band music. Such openness allowed King to create a sonic blend that sharpened the blues’ melodic appeal without dulling its root characteristics.

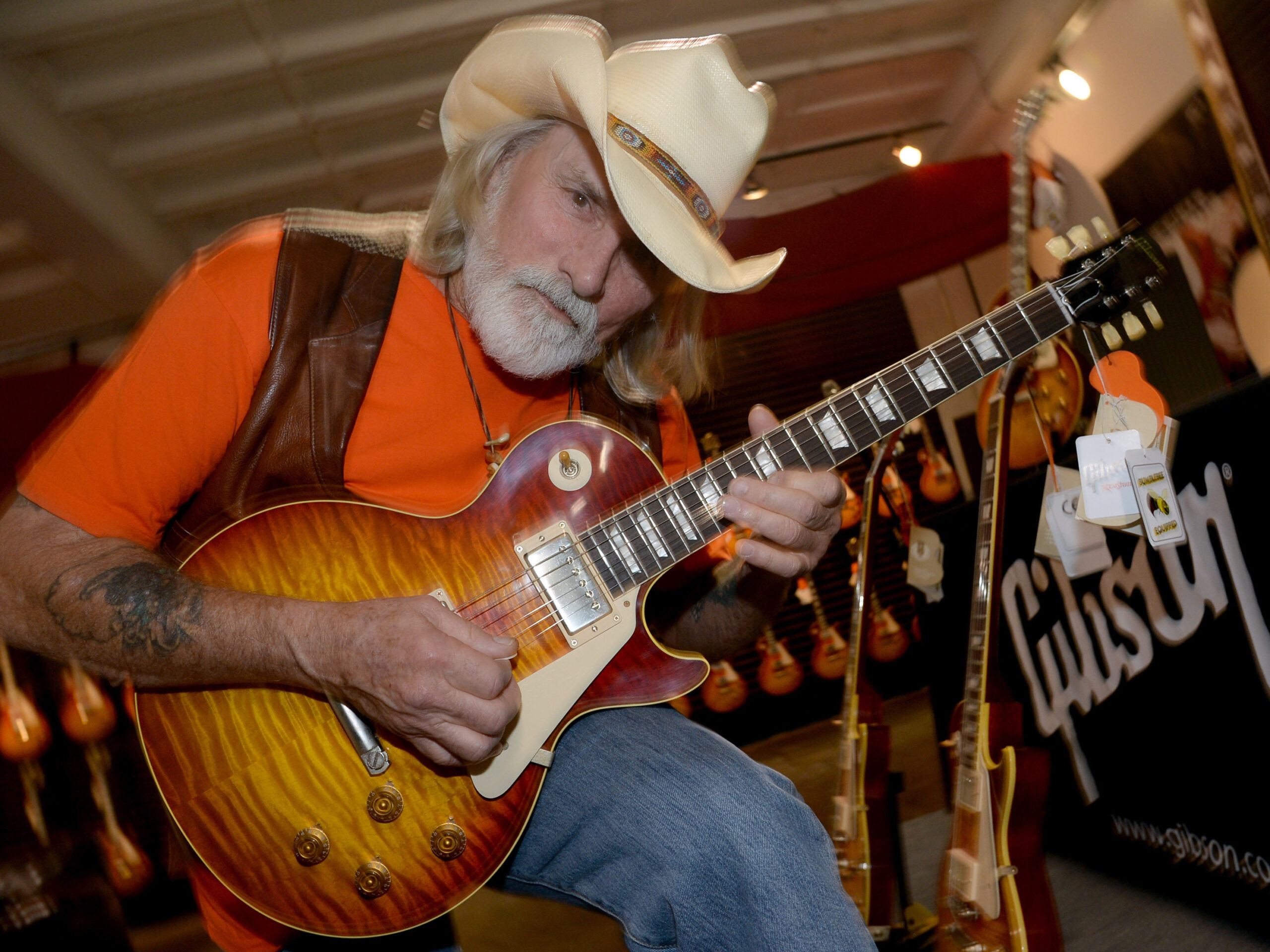

So powerful was the music’s appeal and the seamlessness of this hybrid that few would’ve dared to accuse him of being a sellout. And using his position as blues elder statesman, King was fearless when he collaborated with those decidedly outside the blues, from contemporary rock stars U2 to country star Willie Nelson to jazz fusion guitar god John McLaughlin.

While many of King’s songs frequently featured on any greatest hits compilation offer the essential distillation of his talent, two other, less-well-known songs — “Hummingbird” and “When Love Comes To Town” — give solid evidence of just how expansive his gifts were. Careful listens can hear how King succeeds in being himself despite appearing in songs that are thoroughly out of his normal wheelhouse.

“Hummingbird,” which was recorded with pianist Leon Russell and future Eagle Joe Walsh in 1970 for the “Indianola Mississippi Seeds” album, places King in front of funky, soul-music revue. King thoroughly impresses as a torch-burning soul singer (few songs have offered such a chance to see the extent of King’s vocal range). At the same time King woos with his voice, his crying guitar licks duel effectively with Russell’s gospel-influence piano playing to keep the song from sounding too rote. As the emotion builds, a bombast of string accompaniment and choir of female backing singers lurks near the surface until King beautifully cues them to drive home these overpowering feelings at the song’s apogee.

“When Love Comes To Town” shows King as the perfect medium to channel U2’s mid-1980s explorations of American roots music and to ground it with authenticity. The song appeared on the group’s much-maligned “Rattle And Hum” album. On paper, there are quite a few factors against this track coalescing around King — a tribal-rock rhythm, mishmash lyrics and the Edge’s post-modern guitarscapes — but interestingly, King adds mighty heft that centers the music. His soulful vocals match Bono’s boastful proclamations while his guitar brilliantly quivers and threads through the Edge’s crashing drones. The song is testimony to how King transcends genre and yet never surrenders his personal sound. When the band tried to repeat the idea again a couple of years later in a studio collaboration with Johnny Cash, the results were nowhere near as remarkable.

Hear the songs below: