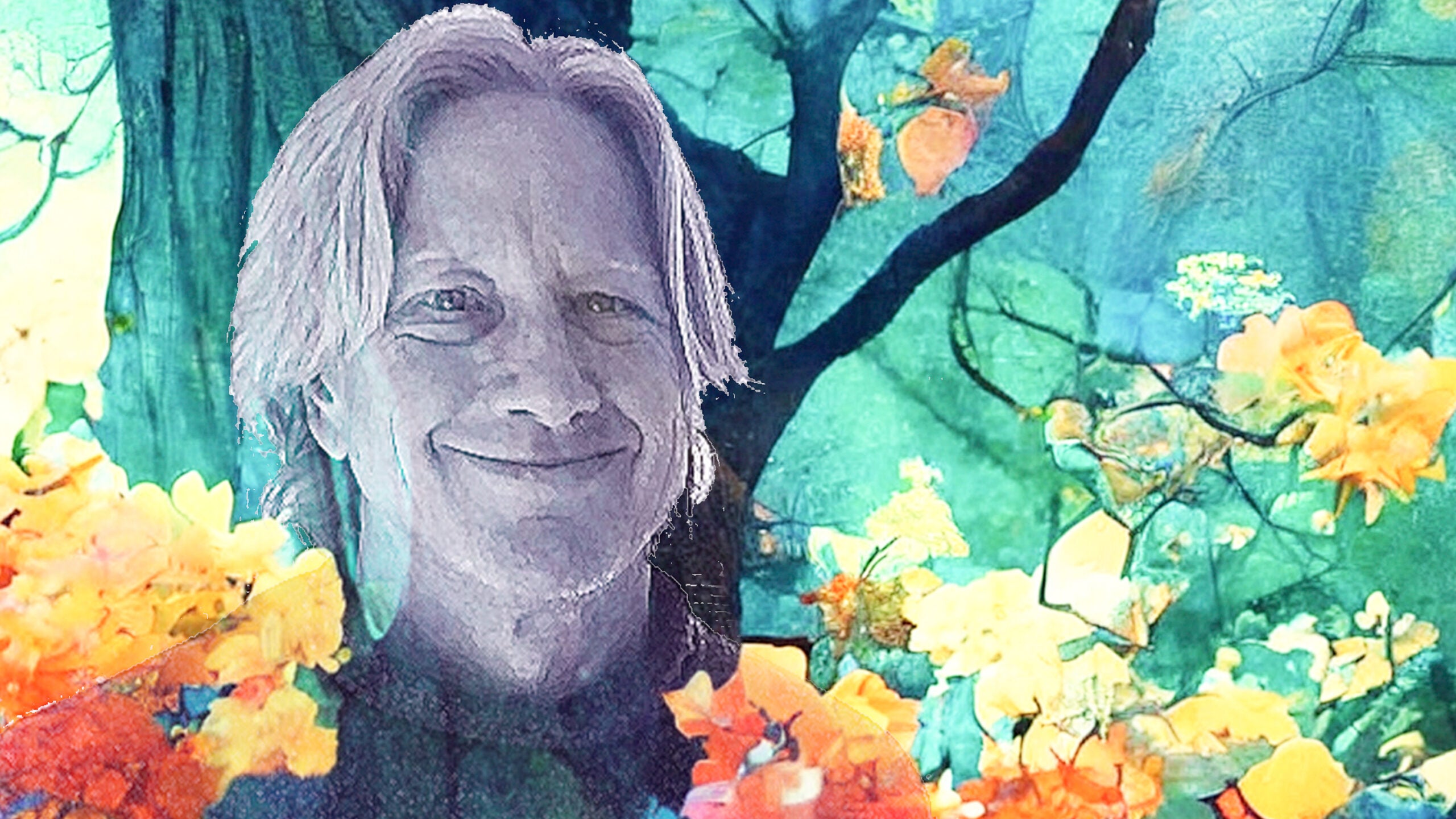

Anthony Bourdain — chef, storyteller and world-traveler who gave regular restaurant-goers a behind-the-scenes look in his evocative book “Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly” — has died at age 61.

Bourdain took television viewers around the world in search of interesting food stories in his shows including “Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown,” which recently began its 11th season on CNN.

Bourdain was opinionated in his dislike of well-done steak, and his adoration for oysters and fois gras. He was known for his ability to combine love and food in most every story, and was fascinated with unfamiliar cultures and hidden delicacies — determined to reveal them to people watching, or reading, at home.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

CNN reported Bourdain died of a suicide in France on Friday.

The food community — as well as his audience of armchair cooks — is remembering Bourdain in an outpouring of heartbroken posts and stories in the media.

“To the Best of Our Knowledge” Executive Producer Steve Paulson interviewed Bourdain in 2004 when he was still the executive chef at Brasserie Les Halles in New York City. Bourdain told Paulson he began his career as a dishwasher, and that being in charge of a professional kitchen was “like the child’s dream of running one’s own pirate crew.”

Listen to Steve Paulson’s interview with Anthony Bourdain.

Interview Highlights

Steve Paulson: What it is like to be the executive chef of a restaurant?

Anthony Bourdain: It’s the child’s dream of running one’s own pirate crew. On the bad side you’re trapped inside a small, hot, airless space with the same sort of criminally inclined characters for most of your waking hours. On the other hand you get to be a leader, to rule over your own radical underlings with very counter-cultural lifestyles.

I get a lot of satisfaction out of that, people whose lives are essentially completely dysfunctional and unlovely outside of the restaurant that they show up to work every day and do great, conscientious work for me — it’s a source of a lot of satisfaction of my life. And, you know, to be a despot for 10, 12 hours a day is fun as well. I am an absolute ruler in my domain. That feels kind of good.

SP: Now your starting in the restaurant business was actually quite humble. Did you begin as a dishwasher?

AB: As a really lowly dishwasher and prep drone. I wash dishes, pots, get sent down to the cellar for hours at a time just to peel potatoes, wash spinach, pick parsley, tear the little beards off mussels, fetch the chef a drink, mop his brow, that sort of thing, you know all purpose flunky and dogsbody.

SP: Is that what you would recommend for someone getting into the business? That you should start at the bottom?

AB: Absolutely. You know as a chef I would hire an ex-dishwasher over a culinary school graduate any day. It’s a character issue. If you work your way up from the bottom, chances are you’re going to be a lower-maintenance employee from a chef’s point of view, and that you know what it’s like to have come up through the chain of command and you also tend to — having worked as a dishwasher — you’ve learned everything about the restaurant and the preparation of the food from the ground up.

I’m just very partial to ex-dishwashers. I find that they make better cooks and they have better character. They’re less likely to consider themselves sensitive artists and require the you know, ego stroking, patting on their head, kissing of booboos, that sort of thing.

SP: Don’t you want artists in the kitchen? Isn’t that what it takes to make great food?

AB: No. Really good cooking in my view is about turning in a consistent performance. Every day, day in and day out, never calling in sick, never showing up late, never giving the chef attitude, never offering helpful suggestions — particularly when you’re in the lower echelons of a kitchen — you’re not really allowed to have a personality or an opinion that’s detrimental to the smooth operations of the restaurant.

SP: This sounds like the military as you’re describing it.

AB: They call it a brigade for a very good reason. Escoffier’s system for managing a kitchen was called the brigade system and it is a very rigid, military-type hierarchy. I think it’s one of the reasons that so many people like myself who are basically disorganized, lazy and chaotic outside of work, feel so at home in the restaurant business, because it’s the only order and structure we have.

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or go to www.SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for a list of additional contacts.