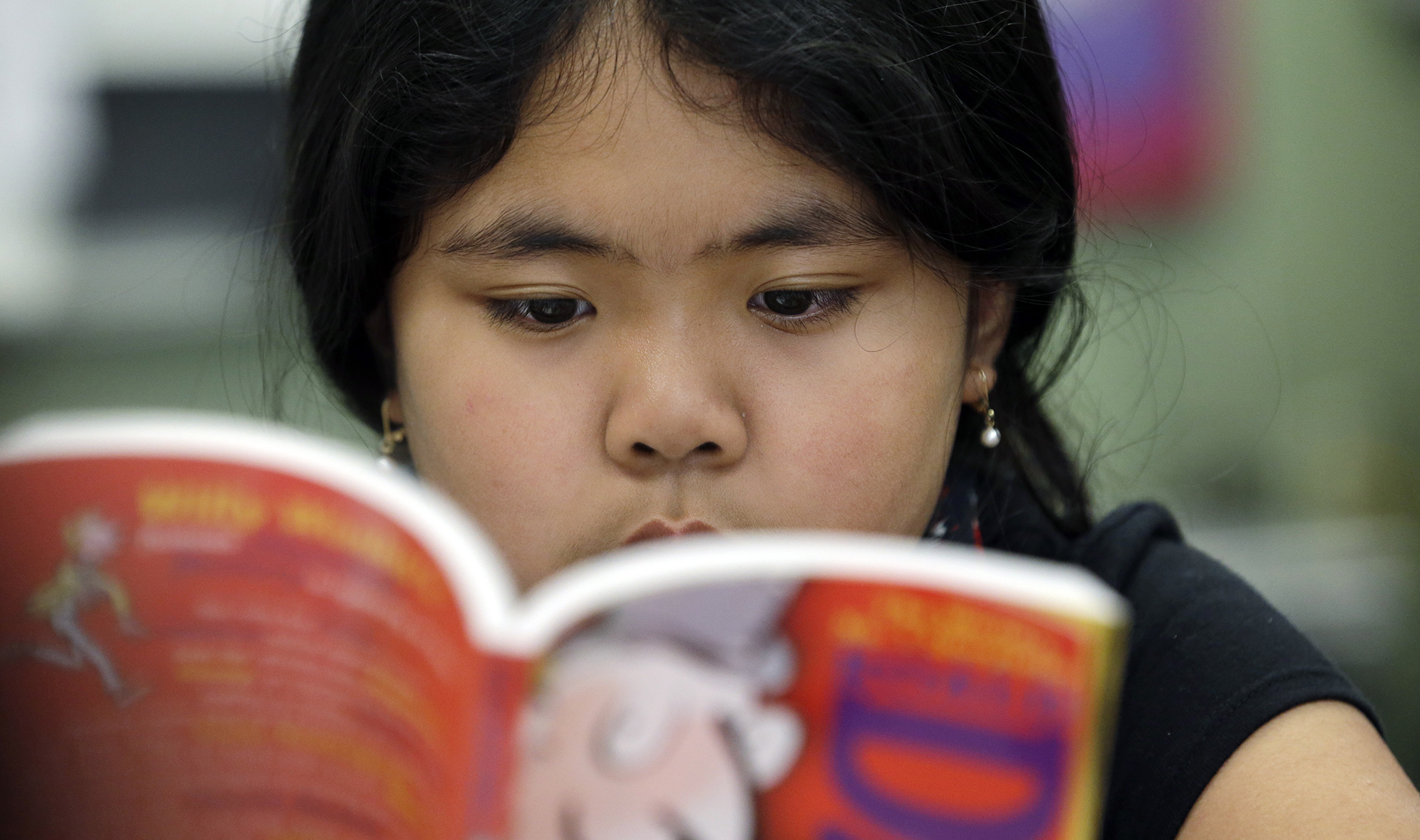

The number of Wisconsin students who qualify for English language-learning or bilingual programs declined for the second year in a row, potentially jeopardizing state funding — which already covers only a fraction of the cost of bilingual and English as a second language education.

The population of English learners in Wisconsin schools grew by 78.6 percent from 2001 to 2019. But the 2019-2020 school year saw a 0.2 percent dip from 51,825 to 51,706, followed by a 2.1 percent drop to 50,630 in 2020-2021 — some of which may have been driven by the pandemic, with overall enrollment in Wisconsin public schools dropping 3 percent this school year.

“For a long time we were seeing this population grow pretty exponentially, and just given the way that Wisconsin does fund the education of English learners, any sort of drop or little fluctuation can have some pretty strong potential implications if it does turn into a long-term trend,” said Maddie Hahn, a fellow at the Wisconsin Policy Forum who co-authored a recent report on Wisconsin’s English learners.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Wisconsin’s funding formula for English learners means that districts only get state funding for ESL and bilingual programs if they have a minimum of 10 students with the same language background from kindergarten to third grade, and 20 students in grades four to eight or high school. In the 2019-2020 school year, that meant that while 361 school districts reported having English learners, only 51 met the threshold for state funding.

Even in districts that do qualify for state funds, the stagnant levels of funding for English learner programs — state bilingual bicultural aids haven’t increased since 2007 — mean that state aid only covers about 8 percent of the cost of bilingual or ESL education, down from about 32 percent in 1995.

“There’s a way in which this hurts both small and large districts,” said Jason Stein, the other Wisconsin Policy Forum study author. “Small districts are hurt by, in many cases, just not having the concentration to qualify for any reimbursement at all, and then your larger districts would easily have enough students to qualify for the program, but because the program only reimburses about 8 percent of costs at this point on average, the large districts would not be getting most of the costs of EL instruction reimbursed.”

Green Bay Area Public Schools has around 4,500 English language learners whose first languages range from Spanish to Hmong to Somali. Within that broader umbrella, it has a bilingual Spanish-English program, with over 100 bilingual staff members including teachers, counselors and clerical aids.

Georgina Cornu Zacharias, Green Bay’s associate director of bilingual programs, said that’s been possible because of decades-long investment at the district level, because state funding has been minimal.

“It is an additional cost, but we think it’s worth it because of the students and the families we service,” she said. “We truly believe that providing this opportunity to the kids is an investment in the future of our community.”

About 22 percent of Green Bay students are English learners. Within that group, Green Bay consistently has about 1,400 elementary school students in its bilingual Spanish program, and around 350 middle school students, Cornu Zacharias said. This year, the district saw a drop in its number of students who qualified for bilingual programs, driven mostly by a decrease in kindergarten and pre-K students — which is part of a larger trend in Wisconsin school enrollment this school year.

Green Bay still has a large enough number of English learners that even with a drop, it’s nowhere near falling below the threshold for state funding. However, in districts that just barely qualified for state reimbursement — as small as it may be compared to the actual cost of English learner programs — a 2 percent reduction might mean slipping below the requisite 10 or 20 students, and having to front all the costs out of the district’s general funds.

Stein said even families without English language learners should worry about the gaps between state funding and districts’ costs for bilingual and ESL programs.

“Whether it’s special education or English as a second language, if there’s students that have particular needs that districts are obligated to serve, if the state provides aid that covers a large part of those costs, the district is free to focus their local resources on other students,” he said. “To the extent that those needs are not met by the state aid, the districts have an obligation to meet those needs, and can find themselves obligated to divert resources from their general funds to cover the needs of those students.”

During the pandemic, English learner and immigrant families were often harder hit by COVID-19, as well. In Green Bay, the large Spanish-speaking population was disproportionately affected by coronavirus outbreaks at Brown County meat processing plants.

“We definitely have seen that our English language learning families were affected by COVID perhaps to a higher degree, and that is true of our communities of color here in Brown County,” said Cornu Zacharias. “We are all dealing with that trauma as a community, and then they’re seeing that in their homes and their families.”

Green Bay has a fairly large bilingual staff that could help families troubleshoot problems with online learning, but in smaller districts, or districts that haven’t been able to support as robust a bilingual program, virtual English learners often had the added difficulty of not having anyone in their family who could help them with classwork in English, or understand login instructions or other tech issues if they weren’t accessible in their home language. Things got even harder if those students also had spotty internet access.

Gov. Tony Evers’ proposed budget included a change to Wisconsin’s English learner funding that would provide $10,000 per student in districts that have between one and 20 English learners, and then $500 more per pupil after 20. If passed, it would be the first increase in bilingual-bicultural aid since the 2005-2007 biennial budget. The state Legislature hasn’t yet finalized its school finance plan, but early indications show lawmakers aren’t likely to go along with Evers’ education budget.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.