A civil liberties group is calling on the Oneida County Jail to reverse its policy banning inmates from receiving letters from friends and family members.

In a new letter to Oneida County Sheriff Grady Hartman, the legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation of Wisconsin writes that the jail’s “complete refusal to deliver written correspondence to all people in the jail is clearly unconstitutional.”

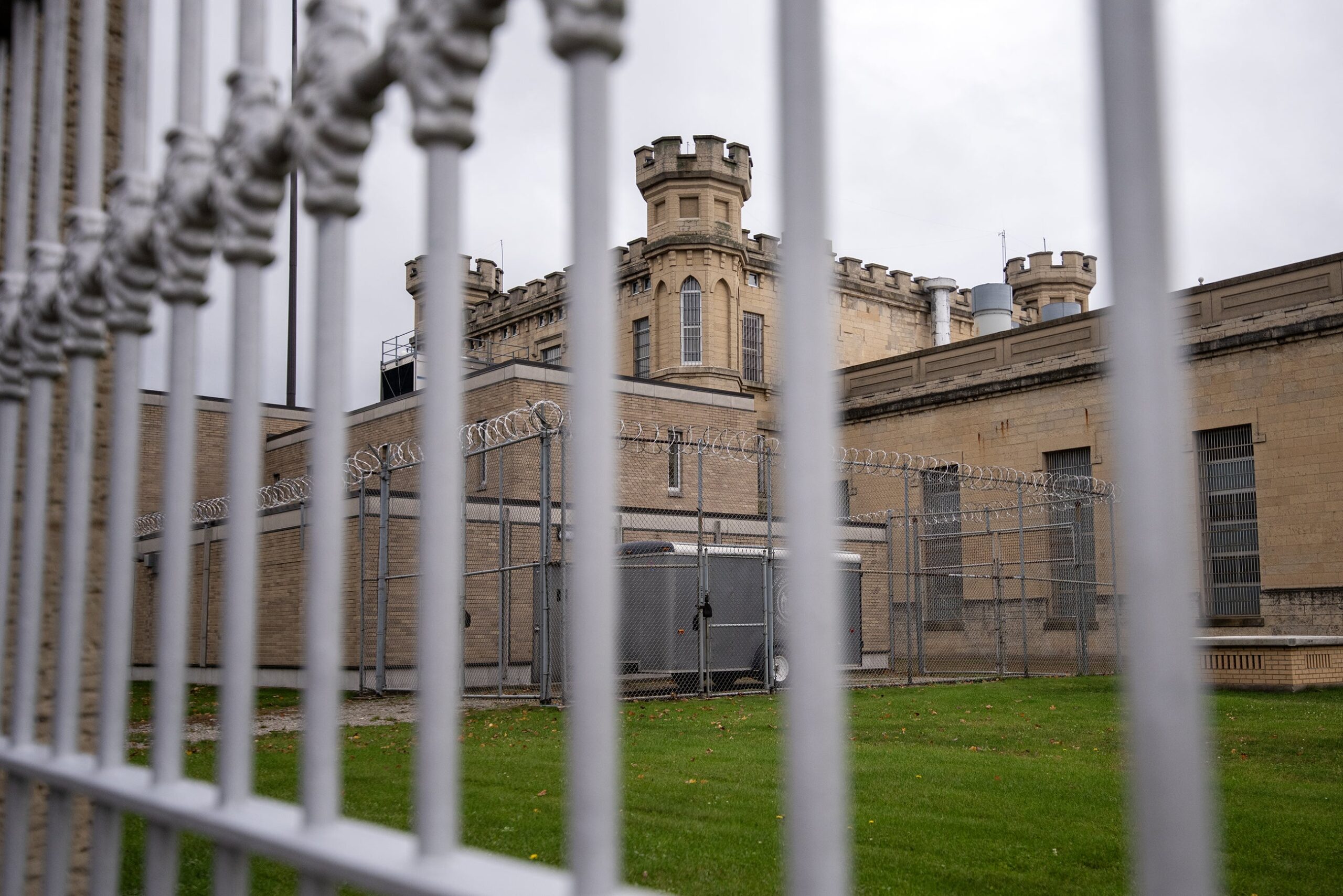

Oneida County may be the only jail in the state to refuse letters from outside friends and family members. It’s a policy Oneida County put in place in 2019 after Hartman said inmates received illegal drugs and contraband cellphones and pornography smuggled through the mail.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“We had inmates smuggling things in that could potentially kill somebody, and so we took action on that,” Hartman said.

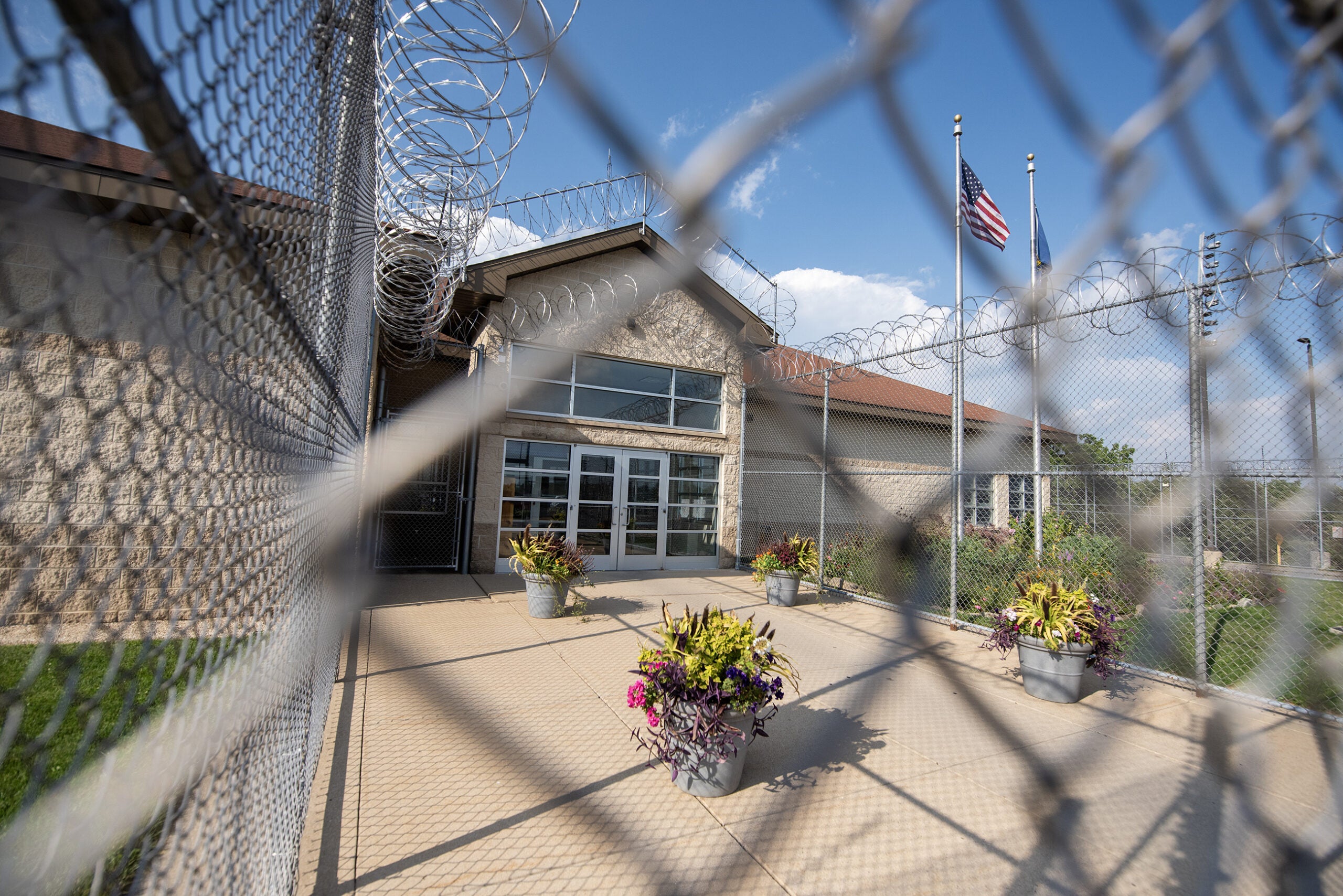

The jail replaced paper mail with electronic kiosks in its cellblocks that allow inmates to receive emails and video calls, for a price. The ACLU has requested Hartman turn over all documents relating to its contract with the private vendor that operates the kiosk service.

In an interview with WPR, ACLU legal director Larry Dupuis said courts have long recognized that inmates have a right to receive mail.

“We don’t want Grandma to not be able to communicate with her grandson … just because the grandparent doesn’t have access to email,” Dupuis said.

The jail has a kiosk in its lobby where visitors can place video calls for free. But most calls happen remotely, and are charged by the minute.

“The reality is a lot of these privatizing schemes end up costing people a ton of money,” Dupuis said. “And it’s money they don’t have to begin with, because they’re in jail or prison.”

Hartman contests the claim that Oneida County’s policy blocks communication, and notes that the cost of receiving a written email through the system is cheaper than the cost of a stamp.

“I do think it’s very important to allow the inmates to communicate with their friends and loved ones,” Hartman said. “That should be a protected right.”

In addition to emails and video calls, Hartman said inmates can have books and magazines they or their families order from publishers. Communications with lawyers, including written communications, are protected, and the jail permits outside mailings from churches or religious groups.

“We don’t cut off everything,” he said. “We cut off personal letters where they could smuggle stuff.”

Still, Oneida County’s policy appears to be more stringent than other jails’. Some jails and prisons have a policy of scanning or photocopying mail and giving inmates the copies in order to prevent them from receiving, for example, letters written on paper soaked with drugs. The federal prison system recently tested a similar policy in its facilities. Dupuis called scanning “potentially problematic” but probably lawful. And he said there’s a sharp distinction between that policy and a rule that simply disallows all letters.

Oneida County Jail has a capacity of around 200 inmates, but its local inmate population is typically well below that capacity. In 2019, usually fewer than 100 people from the Northwoods county were inmates there. The jail contracts with the state and other counties to house inmates from overcapacity state prisons and county jails.

That means its population includes people from as far away as Milwaukee and Racine. Hartman noted that prior to the use of kiosks for video calls, some families had to make hourslong round-trip drives for visits that lasted only 20 minutes and were only allowed once a week. To those who pay for the service, the video chats are available any day and virtually any time.

But Dupuis said the two things aren’t mutually exclusive, and plenty of jails that have contracted with kiosk vendors still allow inmates to receive letters.

Jails, he said, “have dealt with mail for decades, centuries. How hard can it be to keep doing what they’ve been doing with mail?”

Dupuis declined to say whether the ACLU would take legal action, but said the organization is gathering information and weighing its options.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.