A new idea for ending partisan gerrymandering would have political parties divide up legislative boundaries like two people might slice up pieces of a cake.

The proposal, unveiled last month in a research paper by two professors at Carnegie Mellon University, would rely on the self-interest of Republicans and Democrats, who would take turns drawing districts and locking in legislative boundaries.

The approach is different from other efforts to reform redistricting, which often call for the creation of independent commissions to draw the lines.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“If it’s really possible to have an independent commission which is competent and really just has the best interest of society at hand at all times, then that’s probably the best thing that you can hope for,” said Wesley Pegden, an associate professor of mathematical sciences and one of the authors of the study. “But it’s just not clear to me that you can really do that.”

The system Pegden developed with Ariel Procaccia, an associate professor of computer science, is based on the same principles as cutting a cake in a way that’s mathematically fair.

If there are two people, the first person cuts the cake and the second person chooses the first piece. The first person will cut the cake fairly so there’s a good piece left over when it’s their time to choose.

“This is envy-free in the sense that every player likes his own piece as much as he likes the other piece,” Procaccia said. “It turns out that redistricting has a similar flavor.”

In the redistricting plan drawn up by Procaccia and Pegden, one party draws all the legislative districts and the other party chooses one of them and locks it in place. Then the second party redraws the remaining districts and the first party chooses one.

That process repeats itself back and forth until all districts are finalized.

“The nice aspect of it is that even though the process is handled by politicians and is competitive in the sense that every party works in its own interests, we can still prove that the outcome would be fair to both parties,” Procaccia said.

Procaccia and Pegden said they’re hoping that as people find out about their plan, it will become part of the national discussion on gerrymandering and might be adopted by states in future rounds of redistricting.

While some states can rewrite the rules for redistricting through citizen ballot initiatives, that’s not possible in Wisconsin, where any change would need originate from the state Legislature.

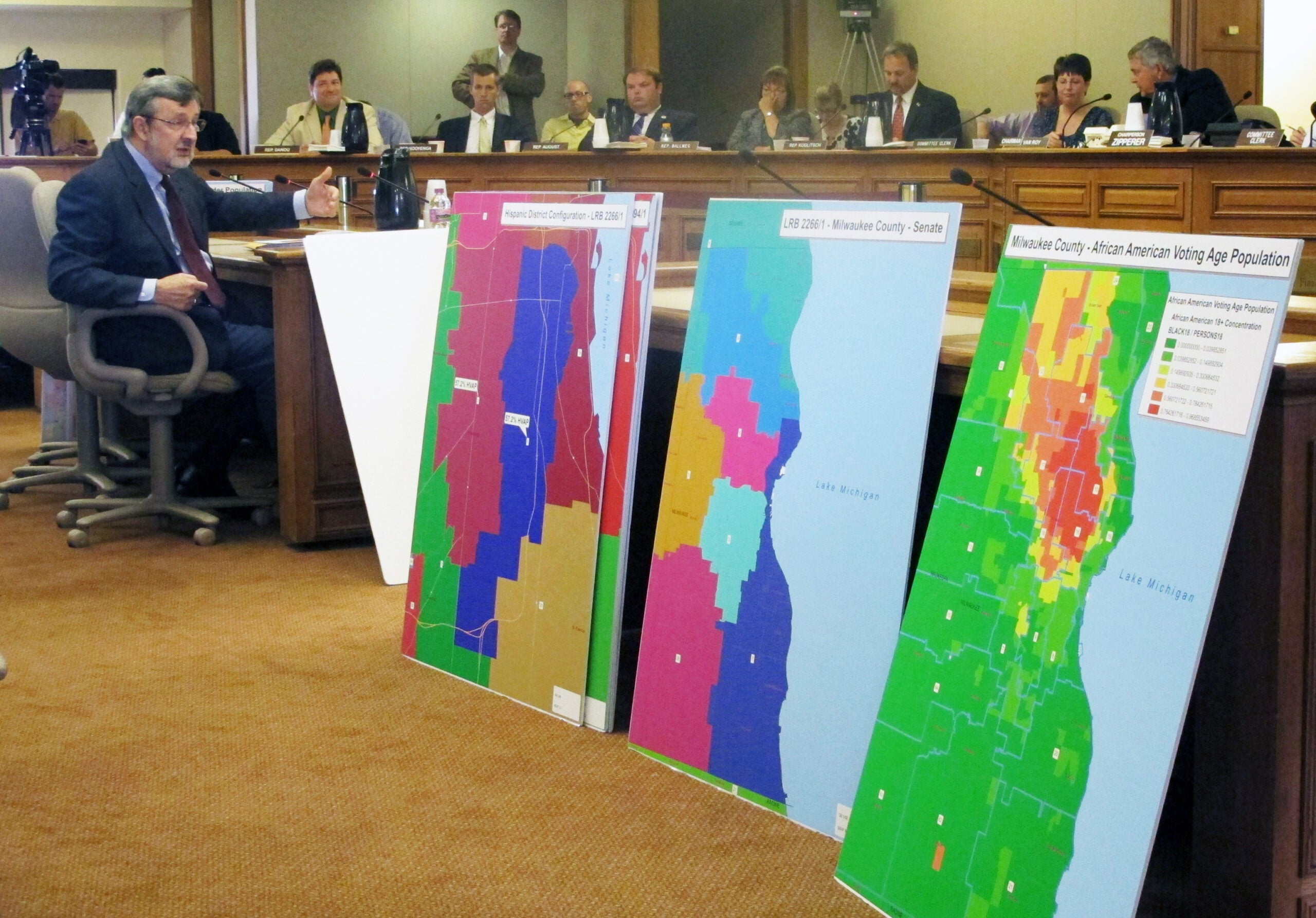

Wisconsin’s current legislative map was drawn by Republicans in 2011 after they won control of both houses of the Legislature and the governor’s office after the last census in 2010.

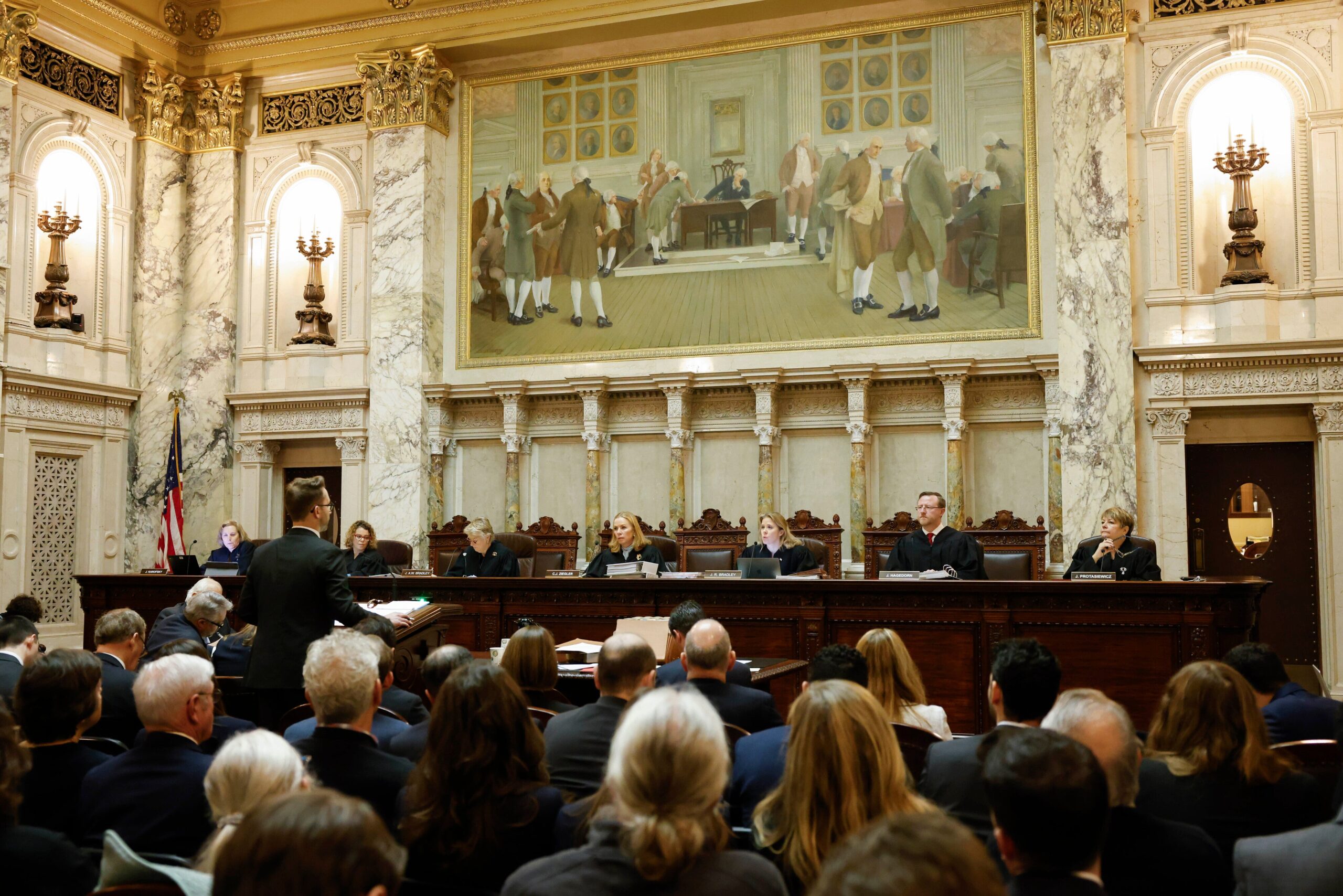

Wisconsin’s map has been at the center of the national discussion on redistricting. The U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments this year in a lawsuit that alleges Wisconsin Republicans were too partisan when they drew the map, and violated the constitutional rights of Democrats in the process.

The court will likely issue a decision in Wisconsin’s case in the first half of 2018.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.