In most cities across the country, so-called community schools are campuses that house services like health clinics and day care centers that can remove barriers to learning. It’s an approach that’s credited for the jump in Cincinnati’s high school graduation rate from 50 to 80 percent.

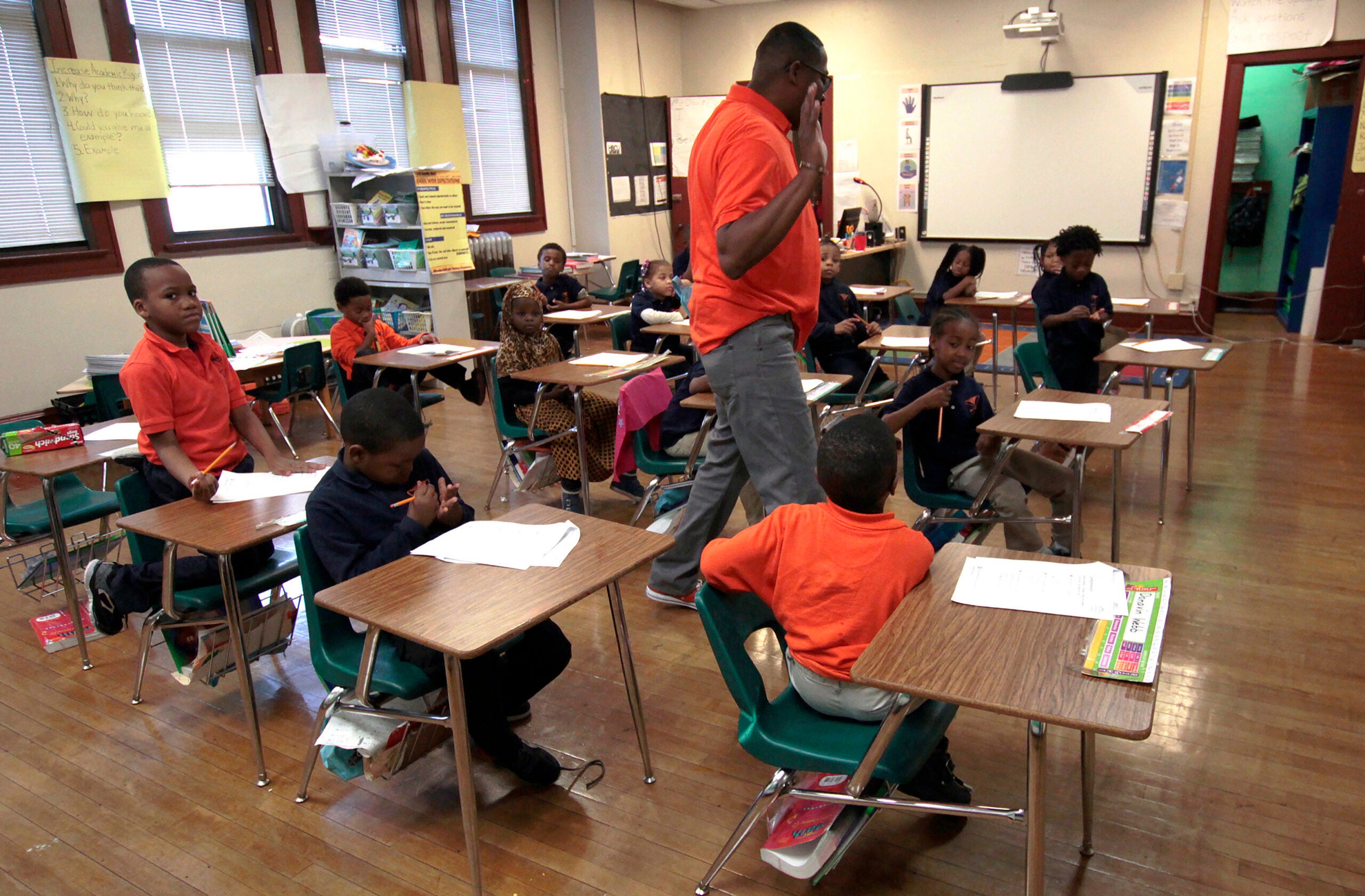

But Milwaukee is taking a slightly different approach. To improve attendance, graduation and student achievement, Milwaukee’s community schools are turning inward and focusing on getting people to talk to each other. In both approaches, the goal is to figure out the needs of each school environment and then meet those needs.

Six schools across the city are part of the Milwaukee Public Schools Community School pilot program. The program pays for a community school coordinator in each school to organize efforts to identify and address student needs on each campus.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

James Madison Academic Campus on the city’s northwest side was one of the first four pilot schools last year.

In the high school, the hallways are quiet during classes and to Gregory Ogunbowale, that sounds like progress. When he became the school’s principal four years ago, fights broke out regularly in chaotic halls full of students who should have been in class.

“We have about 500 students in our cafeteria every morning, when they come to school we’re playing our soft music, I’m moving and dancing to it. They’re making fun of me, and hose kids are not going to fight,” he said. “In the morning when I first got here, before 9 o’clock, we’re talking about six, seven fights.”

The peace and quiet is the biggest change junior Elliyah Lock has noticed since James Madison became a community school last year.

“We still have our little moments when we have fights, but from freshman year where we had fights almost every day, every week, it’s tremendously changed,” she said.

She said she thinks everything started to change when teachers and administrators turned to students for solutions

“You just get picked out, where they’d pull us aside and they’d ask you, A: what goes on. Or one of the students that did get into a fight, they actually sit down and talk to leadership, VFC – VFC is like a violence free zone – so we go there to talk about problems, too.”

Talking, or communicating more, is a big part of what it means to be a community school in Milwaukee. It starts with a meeting, called a community conversation that brings students, teachers, parents, staff and outside partners together to answer questions about what they all want to see their school become, what obstacles exist and how they think the obstacles can be overcome.

As the community school coordinator, it’s Samantha Garrett’s job to find themes in their responses and identify priorities all of those stakeholders can agree on. The three priorities on campus now: communication, programs and partnership, and climate and culture.

Next, she makes sure all of the school’s groups, committees and partners understand the community’s goals for the school and are working toward them together.

“Conversations happen over here, conversations happen over there, but then there wasn’t anybody to connect the two, but they’re talking about the same ideas,” Garrett said. “So my job is to sit in those meetings and say, ‘Let’s work together to do that so we can be bigger, better, stronger together.’”

James Madison has after-school tutoring services, a parent resource center, academic programs focused on finance and health career pathways. Some resources have been on campus for years. But with everyone communicating, Lock knows about a lot more programs than she did when she came to James Madison as a freshman.

“We have more opportunities where we can do stuff to help us with college,” Lock said. “There’s also other after-school programs that helps kids, if you want to swim you can swim, if you want to come and study, you can study here.”

For Garrett, Lock’s awareness of what’s going on and available in the school is what her work’s all about. If the students don’t know what’s offered, then the offerings don’t matter.

“Young people in our building aren’t just kids that are here for us to shepherd through four years without ever talking to them,” Garrett said. “That they feel like decisions get made in the school building that are reflective of them.”

Staff are more plugged in, too. Inside a classroom off one of those quiet hallways on a fall Tuesday morning, English department teachers were meeting to layout common lesson plans.

Across the hall, counselor Ellen Makowski was helping students complete college applications.

“I think before people were doing a lot of really good things in isolation, and I think now we’re finding out more about what other people are doing and how we can support that,” Makowski said. “A lot of these kids are out of an English class. We’re working with those teachers. They know where the kids are and what they’re working on. We’ll try to make sure they make up the work they missed.”

Elsewhere in the school, a parent course on helping their freshmen start high school on the right foot and eighth graders from around the city were touring the building, seeing if James Madison was the high school they’d like to attend next year.

That’s something Lock said didn’t happen when she first enrolled at the school, she’s at James Madison because it’s her neighborhood school and the easiest option for her family. It’s still an option for students to attend their neighborhood school like Lock did, but students can also opt to submit an application to attend any other high school in the city.

“I think that’s a good thing because I want our school to expand as much as possible like educational wise and student wise as well,” Lock said.

The campus is in its second year of operating as a community school and is still ranked on its state report card as “Fails to Meet Expectations.” Much of the data the report card is based on is from two years ago, but even though principal Ogunbowale is happy more students and partners are being drawn to the school, he knows there’s still a lot of work to do.

“Academically, we’re inching up, we are not there, but we are inching up. Attendance is improving. We started empowering teachers. Now the kids are here, you can’t just look at them anymore, we have to teach them something,” he said.

This is the last year pilot funding from United Way of Greater Milwaukee and Waukesha County will pay for community school coordinators at the district’s community schools. The group is partnering with the school district to raise money to keep the staff in place and spread what they’re learning about what works to other schools around the city.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.