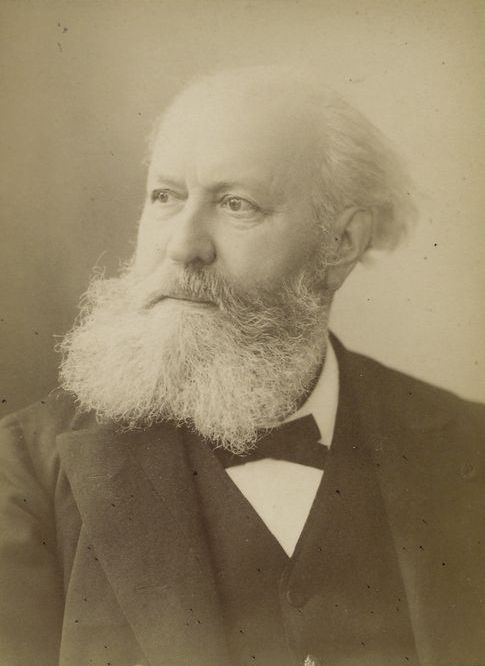

For one reason or another some operas fail to draw crowds. When it happened to Charles Gounod’s opera Faust in London in 1863, the composer was lucky enough to have the services of a clever and daring impresario.

With the opera’s London debut just a few days away, only a handful of tickets had been sold. Impresario James Henry Mapleson was faced with the prospect of a complete failure. He took a bold step and told the box-office manager that Faust would be performed four nights in a row. The box-office manager assured him that he was mad, that one performance of Faust would be more than enough.

Mapleson went even further. He told the manager that for the first three performances of the opera not one ticket would be made available other than those already sold. Then he collected all of the unsold tickets in several carpetbags and mailed them to selected people throughout the city and suburbs of London.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Then Mapleson took out an ad in the London Times, saying that a death in the family had made available at a bargain price some hard-to-get opening night box seats, adding that all other box seats had been sold. He saw to it that the opening night box seats were sold.

In the meantime, people who were turned away at the box office started spreading the word that a Faust ticket was a valuable commodity. As the day of the debut approached, more and more people wanted tickets.

The first performance–well attended by the people to whom Mapleson had mailed tickets–received polite applause. The impresario arranged for Gounod to take several bows onstage just to build up the excitement.

The second performance stirred a little more enthusiasm and by the time the paying public got to see Faust, demand had swollen to the point that the theater was filled night after night—all because of the stratagem of an imaginative and daring impresario.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.