State environmental regulators would be able to set levels for treatment of wastewater that contains PFAS from firefighting foam as part of an emergency rule that was approved by the Wisconsin Natural Resources Board in a 5 to 2 vote on Wednesday.

The rule now heads to Gov. Tony Evers and Department of Natural Resources Secretary Preston Cole for their signatures before it’s taken up by the Legislature’s joint rules committee. Lawmakers could suspend the rule or send it back to the agency for revisions.

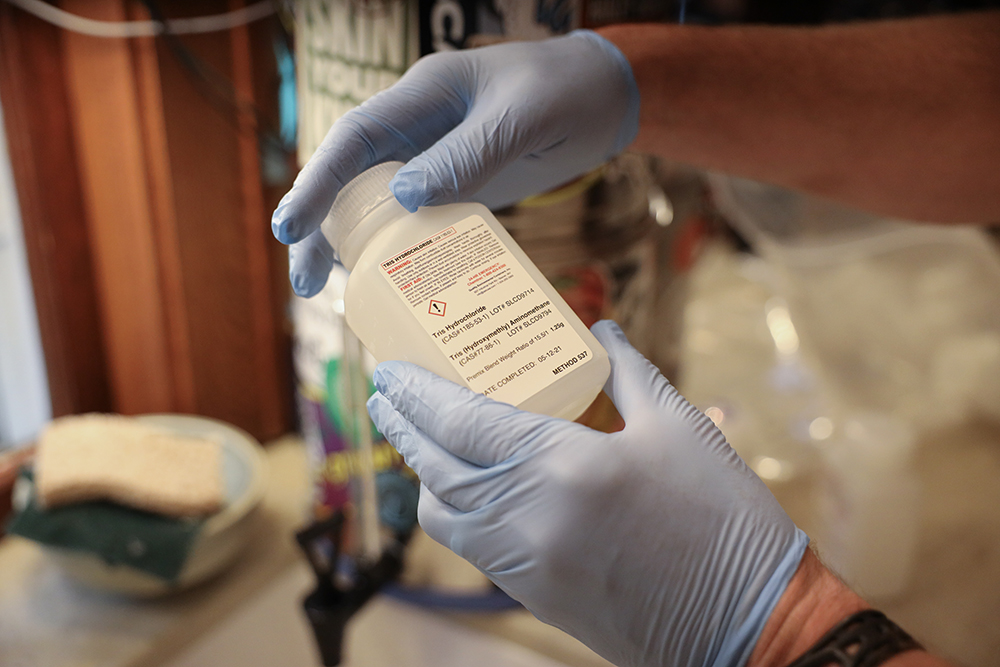

The DNR has been crafting regulations to enforce restrictions under a bill signed into law earlier this year by Evers. The law, which took effect in September, bars the use of foam containing PFAS, so-called” forever chemicals” that have been linked to cancer and other health problems, except in emergencies. The law also allows testing and storage under specific conditions, which include proper treatment and disposal.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

In August, the Natural Resources Board postponed action on the rule after business groups expressed concerns about standards the agency proposed for treatment. The draft regulation set thresholds for appropriate treatment of 14 PFAS chemicals, ranging between 1.3 to 960 parts per trillion.

Sen. Steve Nass and Rep. Joan Ballweg, the Republican co-chairs of the Legislature’s joint rules committee, submitted comments to the board in August that the DNR appeared to be acting without “explicit” authority under the law. They said the proposed standards set up a situation “where the wastewater discharge from an on-site treatment facility has to be cleaner than drinking water.” The two lawmakers highlighted the Wisconsin Department of Health Services has recommended a groundwater enforcement standard of 20 parts per trillion.

Since then, the agency has said those standards will no longer be enforceable. Instead, the levels outlined by the agency would trigger steps a facility could take to meet those limits without DNR involvement. They will be used as an indicator to gauge whether the treatment system is effective at removing PFAS and preventing any release of the chemicals into the environment.

“These are substances that are readily found in firefighting foam around the state, and these action levels that we put in here have been demonstrated to be attainable in Wisconsin and other places,” said Darsi Foss, administrator of the agency’s Environmental Management Division.

Industry groups like the American Chemistry Council and Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce spoke out against the emergency rule, citing the agency’s proposed PFAS limits. WMC argued the agency was overstepping its authority, according to Scott Manley, executive vice president of government relations.

He rejected claims by DNR staff that the proposed standards aren’t enforceable.

“If a testing facility can’t meet these ridiculously stringent standards, they’re required to stop their operations, including stopping any discharges until they can meet those standards,” said Manley. “So basically, if you can’t meet the 14 numeric standards … you’ve got to shut down your operations until you can or change the treatment technology that you’ve installed at significant cost.”

Manley also noted lawmakers rejected inclusion of numeric standards for PFAS during debate on the legislation. Democratic lawmakers urged the state to adopt a recommendation from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services to set a groundwater enforcement standard of 20 parts per trillion. State and federal standards for PFAS in drinking water are still being developed.

Environmental groups like Clean Wisconsin spoke in support of the rule and the action levels set for treatment of the 14 PFAS compounds. Those action levels are “minimal but appropriate” measures to limit PFAS and protect public health, according to Carly Michiels, the group’s government affairs director.

Michiels noted lawmakers rejected an amendment that would have adopted provisions of the CLEAR Act, a separate piece of legislation introduced by Democrats. She said that action should not imply that the agency’s proposed levels are contrary to the law that was enacted.

“These (levels) are based on real performance data from the specified technology treating this material and not based on other state standards,” said Michiels. “Removing (the proposed limits) would eliminate this check and could result in facilities wasting money on treatment that is not working still in the end resulting in contaminated waterways and polluting local communities.”

In a handout, board Chair Fred Prehn outlined concerns with the agency’s proposal to set numeric targets for 14 PFAS compounds, noting it’s difficult to find other states that have set such limits. Prehn and Vice Chair Greg Kazmierski voted against the rule after both raised concerns over whether the agency had the authority to set levels for appropriate treatment.

“I am not anti-clean water. Water has been on our front burner since I’ve been on this board,” said Kazmierski. “However, when we overreach, that prevents us in the future from taking steps forward to having cleaner water.”

The DNR noted in a memo to the board that those compounds represent a fraction of around 5,000 PFAS substances. The DNR also said vendors for treatment technology have said it would be difficult to conduct effective treatment without setting any parameters.

Other concerns about the rule included whether the agency was requiring testing facilities to use technology that may be unnecessarily strict and expensive to achieve proper treatment. The DNR said it required the best available treatment technology in the rule to ensure multiple levels of filtering are used to prevent any release of PFAS chemicals.

The rule also creates an exemption that would allow testing facilities to sample for fewer PFAS compounds if approved by the DNR, and it would also allow operators to phase in changes to treatment as long as the technology being used meets the agency’s action levels.

Community members from the Marinette and Peshtigo area also spoke in support of the rule. The region has experienced PFAS contamination stemming from Tyco Fire Products’ fire training facility in Marinette. The DNR recently said contamination from the facility has resulted in the largest, most complex environmental investigation and cleanup in the state’s history.

Jeff Lamont of Peshtigo said his family has been drinking bottled water for the last three years.

“Frankly, the public is sick and tired of money and profits being put over the health and safety of our community,” said Lamont. “Is clean water really too much to ask for us, for our children and our grandchildren?”

Mike Mikalsen, chief of staff for Sen. Nass, said in an email Wednesday that he still believes some provisions of the rule go beyond the intent of the law.

“Senator Nass will be reviewing the options available to (Joint Committee for Review of Administrative Rules) in responding to the emergency rule, once it becomes effective,” Mikalsen.

A recent DNR survey of fire departments across Wisconsin found nearly two-thirds currently stock firefighting foam that contains PFAS. The majority of those that responded — 63 percent — used the foam as part of emergency response.

Board members questioned whether fire departments may be liable for any release of PFAS-containing foam under the state’s spills law. The DNR’s Foss said departments would not be held liable for any foam released as part of emergency response as long as they notify the agency.

Treatment of firefighting foam containing PFAS that’s used in testing may cost around $7,000, according to Dave Johnson, vice president of operations for environmental services firm North Shore Environmental Construction. He noted the cost to dispose of that foam may cost up to $10,000 per fire department.

The president of the Wisconsin State Fire Chiefs Association has said most departments are storing foam until they receive financial assistance to dispose of it. A foam collection effort and funding are being considered by the Wisconsin PFAS Action Council as part of efforts to help reduce the risk of contamination statewide.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.