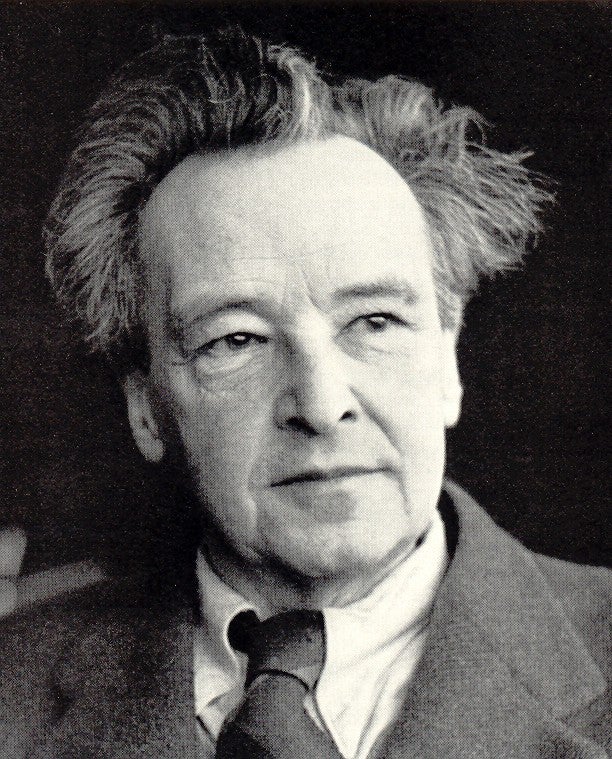

Many young composers would’ve found the offer irresistible: An excellent salary, little responsibility, and plenty of time to write music. And Arthur Honegger received the offer from a very reliable source – his father.

Years later, in 1951, Honegger reflected that several career paths are open to a composer: A professorship, a civil service position, virtuosity, or writing for the movies. If the composer plays the piano like Rachmaninoff, the violin, like Enesco, or the organ like Marcel Dupre – he is “saved.” Or, Honegger reasoned, if he has won a solid reputation in operetta – it’s not impossible that some producer might add spark to his next film by listing the composer in the credits for dashing off a couple of tangos or some waltz tunes.

Then Honegger added, “there’s the theoretical possibility of a guaranteed family fortune. A father who’s an industrialist, a businessman or merchant, who just might help his son to pursue a profession that might bring him success – but not a living.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

In that instance, Honegger was referring to himself. His father was the manager for a large coffee-importing firm in Le Havrc. When young Honegger finished school his father told him, “You are entering the firm. You’ll have very little to do. In the morning you’ll spend two hours at the Exchange. In the afternoon you’ll sign your correspondence. And the rest of the time you can compose music.”

Honegger turned him down. “I was young,” he said later, “full of enthusiasm and ridiculously conceited. I said to myself, ‘Schubert, Mozart or Wagner would never have accepted such an offer. Sell coffee and compose “The Erlkonig,” The Magic Flute, or Parsifal? They don’t belong together!”

His parents graciously accepted his decision, which proved right on two counts. First, World War 1 ruined the coffee merchants of Le Havrc. And instead of grinding out a living as a second violin in Le Havre’s “Folies-Bergere,” Arthur Honegger succeeded as one of the twentieth century’s leading composers.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.