A health care project with a goal of speeding up health research is in search of 100,000 volunteers in Wisconsin.

The state effort is part of a larger campaign, All Of Us, that is hoping to enroll 1 million people across the country who will provide access to their electronic health records and other data that will populate a bank of health information.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health, the program has partnered with the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Marshfield Clinic and the Medical College of Wisconsin to recruit Wisconsin volunteers of diverse backgrounds.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

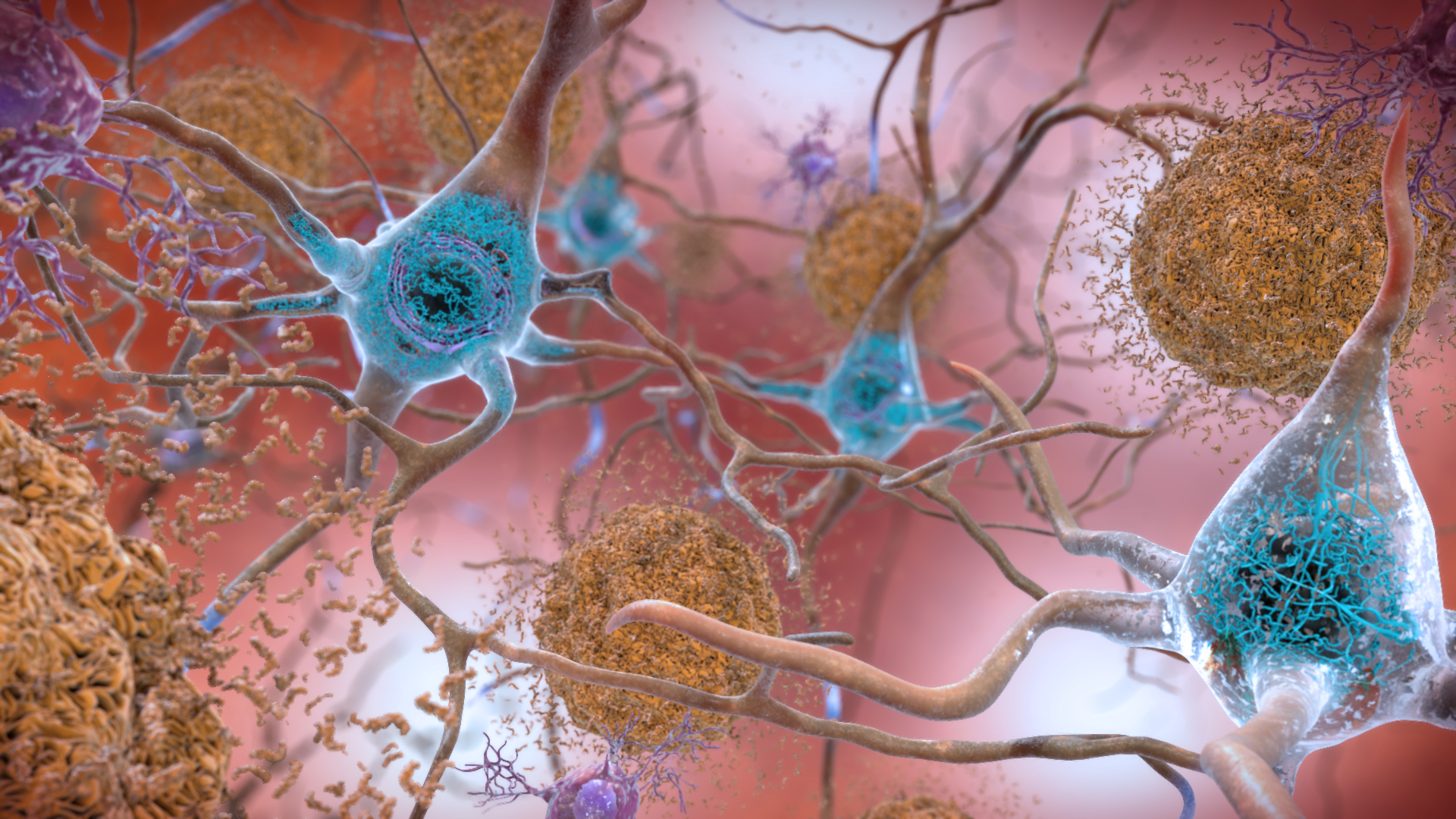

Scientists have a specific goal for the data collected, explained Dorothy Farrar-Edwards, a principal investigator for the All of Us-Wisconsin. That’s to look for patterns in DNA in search of medical breakthroughs.

It’s a launching point into a specific area of care called precision medicine where prevention, diagnoses and treatments are tailored to a person’s genetic characteristics.

“In order to be able to do that more effectively, we need a lot of data from a lot of people in order to drive this process forward,” Farrar-Edwards said.

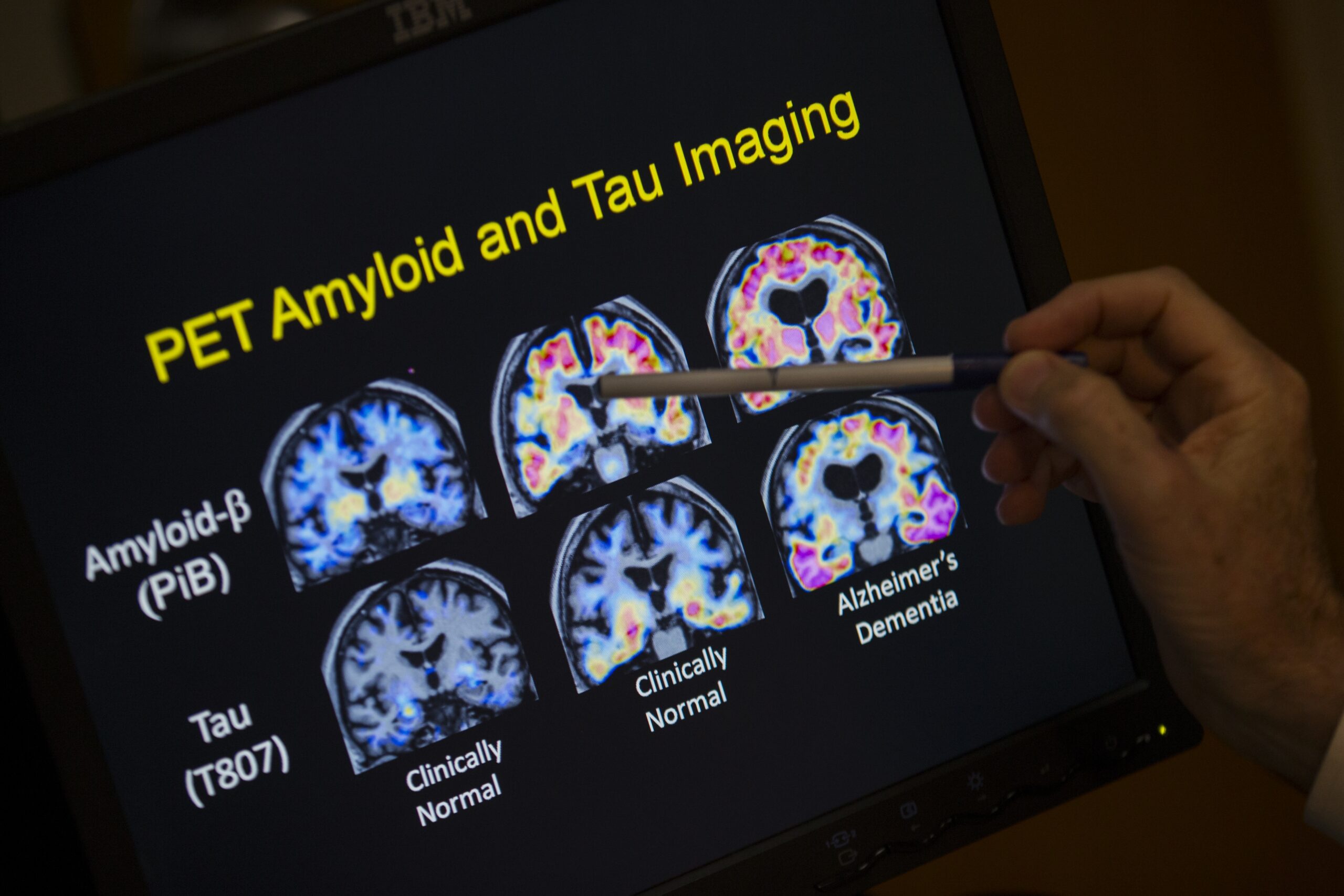

Researchers know there are genetic components to many types of chronic diseases, she said. For example, African Americans are at a significantly greater risk than Caucasians for developing Alzheimer’s disease. This research could help point to why, she said.

Tricia Denman, the research project manager for All of Us–Wisconsin, said funding for the project is tied to recruiting 40 percent of participants from underrepresented groups including those in rural populations, those with low socioeconomic status, those who identify as LGBTQ, among others.

People who want to participate in the study won’t be turned away, even if the 100,000 threshold is met. To get started, volunteers can go to the program’s website and create an account with an email address or phone number.

The website then takes participants through an enrollment and consent process, ensuring volunteers understand what they’re agreeing to.

Participants will be asked to consent to access their electronic health records before taking a questionnaire with basic information such as lifestyle habits, where they live and work. Blood and urine samples will be collected, too, and a full genome sequence will be completed on every participants’ DNA.

If the volunteers agree, the findings from the research will be returned to the individuals.

Denman said one of the project missions is to empower people to have more information regarding their own health care. While no information collected from the study will go into participants’ electronic health records, Denman said participants are encouraged to bring new information to their doctors.

The NIH may follow participants for 10 years, though they currently have enough funding for five. Methods are being built to pull data from Fitbits and Apple watches, and the NIH will pull data from medical records over time to see what changes have occurred.

The researchers understand that privacy is a big concern. The No. 1 question Denman gets is about whether the information is secure.

The different data collected — in questionnaires, blood and urine samples — will be kept in locations separate from the patient’s personal information such as their names.

The program has a certificate of confidentiality, which means no one can subpoena the data.

“We can never say 100 percent, because there is a potential for something to happen, but it’s probably as safe as you’re going to get ever,” Denman said. Nationally, 160,000 people are currently enrolled and about 250,000 have signed up to participate.

Farrar-Edwards said she joined as a participant because she has hypertension and her brother died at age 42 of a heart attack.

“In my family, heart disease is a big problem, and I wanted to understand why,” she said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.