The Milwaukee Health Department set up one of its pop-up COVID-19 vaccination clinics at the Washington Park branch of the Milwaukee Public Library at noon on Wednesday. By the end of the first hour, it hadn’t administered a single dose.

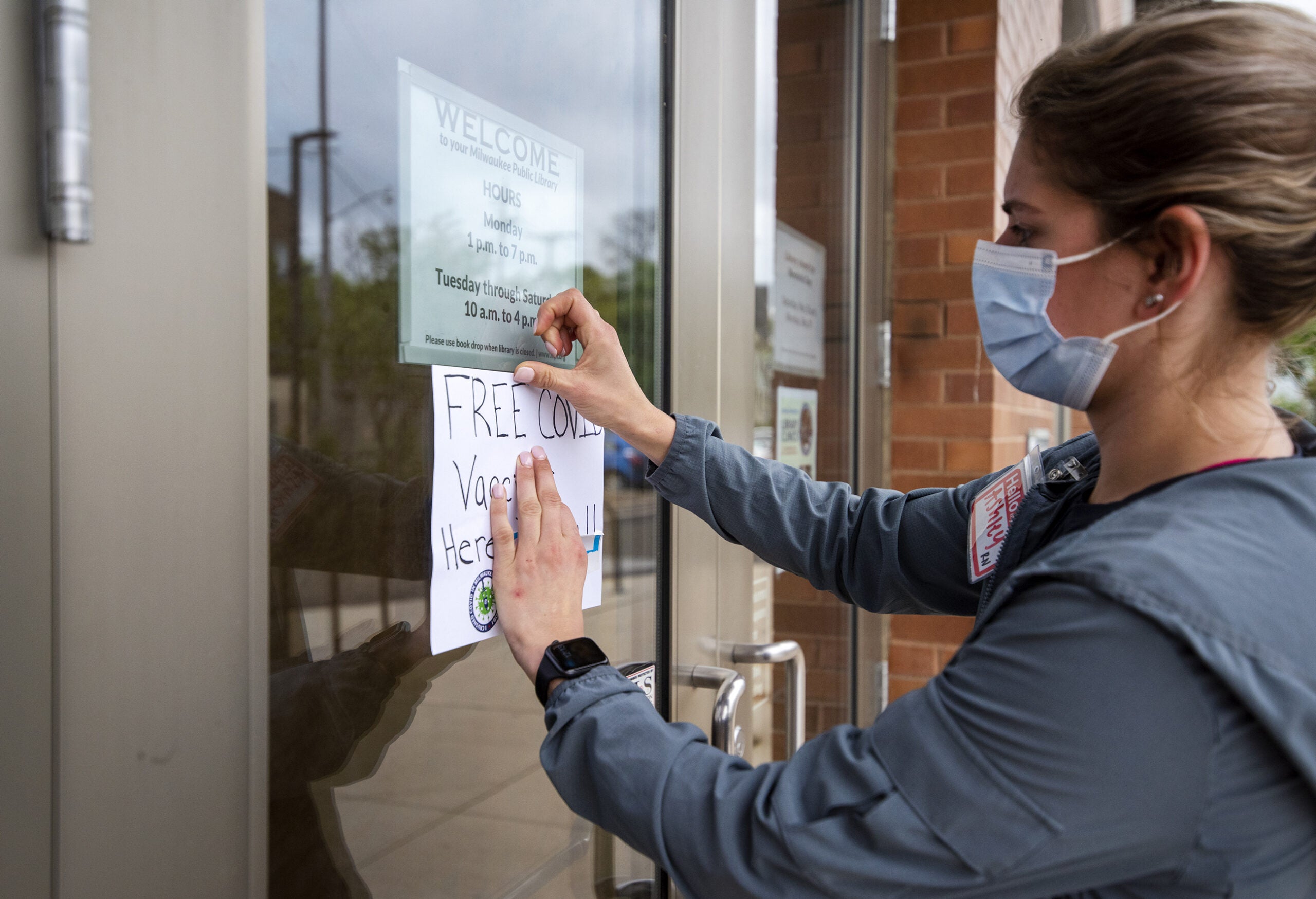

The nurses stationed there hand-wrote signs and posted them on windows and at the welcome desk, then walked around the building to talk to people and direct them upstairs to the pop-up clinic. No takers.

A little before 1 p.m., Nick Tomaro, preparedness coordinator with the health department, packed some of the site’s vaccine doses into a cooler to send a couple blocks away, to another county vaccination site at the United Methodist Children’s Services food pantry, which was seeing more foot traffic.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“We’ve removed a lot of staff from our health centers and moved them to these smaller sites,” Tomaro said. “From our standpoint, we now realize we have to go super small, everywhere.”

Milwaukee County is lagging behind its neighboring counties in vaccination rates. The WOW Counties — Waukesha, Ozaukee and Washington — have all vaccinated 80 percent or more of their residents age 65 and over, while Milwaukee is at 77 percent. Waukesha has vaccinated 46 percent of its total residents, and Ozaukee has vaccinated 49 percent — a full 10 percentage points higher than Milwaukee’s 39 percent.

It’s not unusual for vaccination rates to vary between counties. The New York Times’ vaccine tracker shows variations across Wisconsin, including some areas where crossing the county line means a 20 percentage point drop in vaccination rates.

However, polls show that willingness to receive the vaccine closely correlates with political affiliation, with Republican men the least likely to want a COVID-19 vaccine. Milwaukee is a heavily Democratic county, while the WOW counties are one of the state’s Republican strongholds.

Paul Farrow, Waukesha County executive, said politics is just a small piece of the puzzle.

“If people were looking on political lines, they would say, well then you guys shouldn’t be very high,” he said. “Well, there’s other things that people are considering other than just their politics — they’re looking at their quality of life and safety for their family as they’re vaccinated.”

Farrow said Waukesha County also has a large population of residents working in health care fields who were part of the first vaccination group, which helped get a lot of shots into arms early on. In that respect, he said, Waukesha County is similar to Dane County, which leads the state in vaccination rates.

“The health care providers that we had in the area did a fantastic job kicking it off, and then were able to step in with our clinics and continue the process,” he said.

Farrow noted that based on the data Waukesha County had going into the vaccination process, county officials were expecting about 20 to 25 percent of county residents to decide against getting vaccinated for various reasons. About 50 percent of the county has gotten at least one dose of the vaccine, so Farrow said the focus now is on closing the gap between that 50 percent and a goal of 75 to 80 percent, in part by setting up smaller community vaccine sites like those in neighboring Milwaukee County to increase access for people who want the shot, but haven’t been able to get it yet.

Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett said last week that the rates of vaccination within Milwaukee County vary, but frequently correlate with wealth, and, relatedly, with education and income. That puts it in line with previous studies that showed higher vaccination rates in wealthier communities.

“Those neighborhoods … with higher education, with higher income have a higher vaccination penetration rate than those with lower income,” Barrett said. “Some of this is education, some of this is access.”

Milwaukee County’s median household income is about $50,000, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, compared to Waukesha’s $87,000, Ozaukee’s $85,000 and Washington’s $78,000. Higher-income jobs often come with more flexibility and sick leave, both of which lower the barriers to getting a COVID-19 vaccine and dealing with any resulting side effects.

The rate of people without health insurance is also twice as high in Milwaukee County as in the other three counties, according to census data. Although the vaccines are free — a point the vaccinators at the Washington Park library highlighted in their handmade signs — not everyone is aware that they don’t have to pay to be vaccinated.

Milwaukee is expecting $394 million from the federal American Rescue Plan to put toward vaccination efforts. Barrett said the city plans to focus on efforts like the Washington Park library site — smaller locations close to communities with lower rates — as well as partnerships with churches, nonprofits like the UMCS food pantry, local businesses and even the city’s Mexican consulate, which hosts a vaccine clinic on Fridays.

Tomaro, with the city health department, wasn’t too distressed by the lack of visitors to the library vaccine clinic. The health department is ordering more signs to replace the quick hand-written notices, which he said will hopefully draw more people in, but it’s also putting its eggs in as many baskets as possible — lots of small pop-up sites in other community locations, as well as home visits for people who can’t make it to a clinic.

“We’re trying to be present where people are, and we’re looking at census tract data to say, ‘OK, these are neighborhoods that have low rates of vaccine administration, what are the barriers’ — and we’re going to take vaccine right to those neighborhoods,” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.