Short story master George Saunders talks about his latest collection, “Liberation Day.” Comedian Kevin Nealon on creating caricatures. And Alyse Knorr tells us about the lasting legacy of the N64 classic “GoldenEye 007″

Featured in this Show

-

George Saunders: 'In each of these stories, there's some kind of resolution to fix things once and for all'

Time Magazine has described George Saunders as the “best short-story writer in English.”

We’re willing to bet he’s one of the best short story writers in any language.

His latest collection is called “Liberation Day.” It’s his first since the critically-acclaimed collection, “Tenth of December,” which was released in 2013. “Tenth of December” was a National Book Award finalist.

Is it possible that Saunders’ latest collection is even better than his previous one?

Yes, dear reader. Yes, it is. He recently spoke with Wisconsin Public Radio’s “BETA,” and we’ll make our case.

There’s something very special about a George Saunders story. There’s his trademark humor, his love and respect for humanity, and the kindness and tremendous empathy that he shows for his reader.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Doug Gordon: Why did you decide on the title, “Liberation Day,” for this new book?

George Saunders: At the end of a book of stories, I just look at all the titles of the individual stories. And the assumption is that one of those will be the book title. What I’ll do is I’ll put each of the stories on a separate index card and put them on the kitchen counter and kind of just think through it with that proposed title in mind.

And when I got to “Liberation Day,” something kind of sparked because I think in every one of the stories, there’s somebody who is kind of fed up with the way things have always been for him or for her and wants to make that big change. You know, that that one we all long for afterwards would be completely happy and high-functioning and not neurotic. And so in each of the stories, there’s some kind of resolution to fix things once and for all. Mostly those don’t go that well because we’re human beings.

But what I’ll do is I have the title in mind, kind of scan each story and see if there’s any relation at all between the book title and the story. And there’s just a little click. I feel like, ‘Oh yeah, that, that’s speaking to that.’ My whole process is very intuitive. And the assumption is if I can go through it and keep changing things until I like it more, then the whole project will be saying more in the end.

DG: And I think that the assumption is right. Your editor, Andy Ward, says that “Liberation Day” is yet another step forward in your evolution as a writer. How do you think your work has evolved over the last 10 years?

GS: I suppose as you get older, you become a little more confident in your view of things. You know, you sort of lived through pretty much all there is to live through. So I guess I feel like, well, if things feel a certain way to me, there must be some validity to that. I think as I’m getting older, I’m feeling more convinced that people are quite capable of communicating about the deep things, that all the kind of (superficial) things that divide us really are real, and they’re true, and they have to be dealt with.

But under there, there’s a quality of something — I would call it humanity, really. So if I’m more confident that if I speak to that part of you, that part of you will rise to meet me. And it’s just kind of a quiet confidence from tens of thousands of interactions with people. Whereas when I was younger, I think I wasn’t so sure of that. And so there is a slightly defensive thing you do as a younger writer, which is to be really smart, fast, funny, cynical. All those things have their value.

But I think they also tend to be like moves to keep the reader at bay as opposed to the moves I’m trying to do now, which are to embrace the reader and say, ‘Yeah, you know, it’s like that for me, too.’

DG: You’ve said that “the basic idea of a short-story collection is in line with your view of the world.” So how do you think “Liberation Day” reflects your worldview at this moment?

GS: When you’re writing short stories, they don’t take seven years to write one story — or they shouldn’t. Sometimes they do, but theoretically they’re quicker than that. So in a sense, what you’re doing is you’re kind of saying to yourself, OK, how do you feel during this period? Let’s make up a situation, even a really silly one, and let’s just live in it day after day after day with a lot of concentration. And let’s see which part of you that story represents.

And when you turn to another one, how do I feel now? And you do it again. And so by the time you’ve done nine of these, it’s a pretty good, kind of maybe slightly distorted or exaggerated snapshot of where your mind was during those years.

And the thing that I love about it and that intrigues me so much is it’s not really a snapshot that I would have predicted. If you asked me now, ‘Write a short essay on how you feel,’ certain things would come out, but in the stories, they come out in these crazy ways that are somehow more truthful than the story I can tell myself about how I feel.

DG: I think that the story “Love Letter” gives us a really good sense of where your mind is at these days. Can you tell us about it?

GS: There’s the surface mind and the deeper mind. That story is very much where my surface mind has been.

It’s just really kind of a letter from a very loving grandfather to his probably 20-year-old grandson. Things have gotten worse. There’s kind of a vague dictatorship in place in the country, a right-wing dictatorship. And this grandfather, we feel he’s been chided by the grandson in a previous letter for not doing more, for being kind of passive and having his head in the sand.

So this letter is the grandfather’s response in which he very gently tries to explain to his grandson how this terrible change in American politics happened, sort of on his watch. Just before the last election, a lot of my feelings about myself were in that story. Why am I not doing more? Why do I not know what to do? Why is it that whenever I try to do something, it seems to have no effect? Are we really going to let our democracy sink into the muck with this little feeling about it?

So that was the beginning of the story. You put that in there. You know, then again, because it’s only part of my feelings, then I just attribute it to this grandfather who is not me. And then this story starts to distinguish him and starts to kind of attach to him, I think, a little bit.

There are things that are right out of my life, which I don’t usually do. And it felt really nice to kind of say, “I’m anxious. Here it is.” And send it to The New Yorker and say, “Does this connect with anybody over there?”

DG: And if I’m not mistaken, you had intuition about the grandfather. You knew the kind of voice you wanted to use for the grandfather, but you weren’t sure what the grandfather should do in the story. So how did you deal with that?

GS: One of the things I do when I’m writing is you put something out. And I’m a real obsessive rewriter. So I come back and read it again and again and again. And what will happen is, as you’re reading it, you’ll notice kind of, I guess I would say, a chink in his armor, the character’s armor. So the character is asserting one thing, but under there, you might detect a little uncertainty. And that’s where you kind of dig in.

So with this guy, he pretty confidently explains almost logically, well, yes, this is how we lost our democracy. And maybe it’s not that important, actually. Maybe we just have to enjoy our lives and so on.

But I started noticing little, kind of almost like verbal tells or tics that he was protesting too much. So then you start to lean into that and you say, OK, wait a minute, this guy is saying these confident things, but behind there, he’s got a doubt. And then you start urging the story in a direction that will test him. So in the story, he finds out that his grandson is about to do something a little bold and a little against the law and a little rebellious. And he’s against that.

But then as he starts to kind of piece the thing together in his mind, he sees that the grandson is trying to rescue the woman he loves from the clutches of this dictatorship. I think in the last few paragraphs, just lightly, you feel the grandfather getting really wobbly about his views suddenly.

So the story he’s told himself for five, 10, 15 years under the pressure of his love for his grandson, starts to crack a little bit. And by the end, he sort of tentatively offering to fund this venture. Maybe, we feel.

-

From comedian to caricature artist, Kevin Nealon exaggerates

Kevin Nealon spent nine years as a cast member of “Saturday Night Live.” During his time working “live from New York,” he played such characters as Mister Subliminal, the Austrian muscleman Franz who was ready to “pump you up,” and Mister No Depth Perception.

He’s a very successful stand-up comedian and has acted in Adam Sandler movies and on the Showtime series, “Weeds.”

[[{“fid”:”1801886″,”view_mode”:”embed_portrait”,”fields”:{“alt”:”Kevin Nealon”,”title”:”Kevin Nealon”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”3″,”format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3E%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20Kevin%20Nealon%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Kevin Nealon”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Kevin Nealon”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“3”:{“alt”:”Kevin Nealon”,”title”:”Kevin Nealon”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”3″,”format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3E%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20Kevin%20Nealon%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Kevin Nealon”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Kevin Nealon”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Kevin Nealon”,”title”:”Kevin Nealon”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”3″}}]]

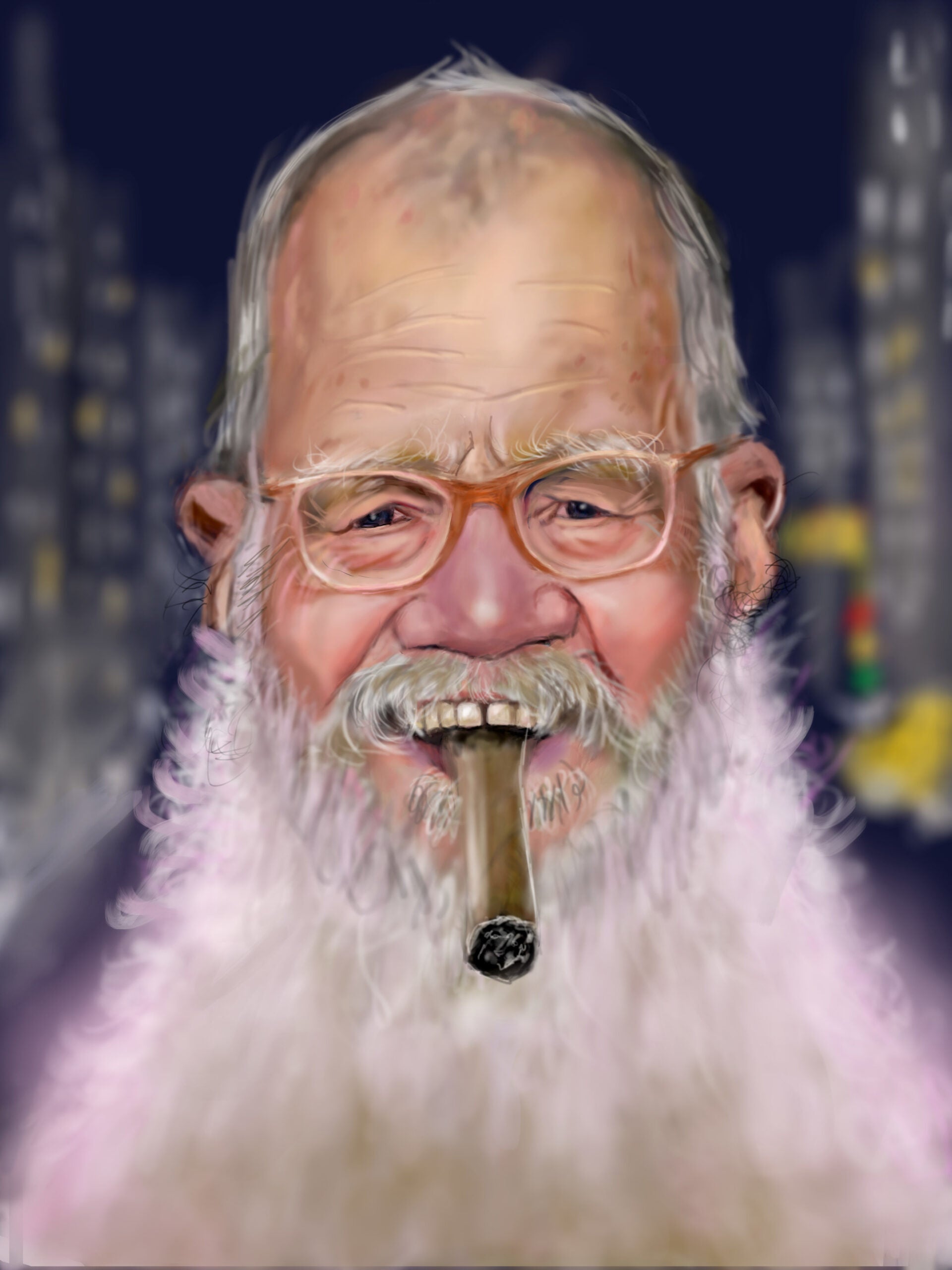

But Nealon is also a very talented caricature artist. His new book, “I Exaggerate: My Brushes with Fame,” is filled with caricatures of celebrities and friends like Chris Farley, David Letterman and even some people that he doesn’t know. Nealon shares a story for every caricature and why he was inspired to create it.

Nealon told Wisconsin Public Radio’s “BETA” that he became interested in drawing early on, when he was about 8 years old. He had seen a sketch someone drew on a napkin at a café that they left on the table.

“It was just a simple face, like a big nose and a hat and a big chin and puffy collagen type lips,” he said. “And I was so amused by that.”

Kevin Nealon’s caricature of David Letterman. Photo courtesy Kevin Nealon So he copied the drawing.

“I wouldn’t trace it, but I was copying it,” he said. “And for some reason, that stuck in my head. And ever since then I just started drawing and started drawing. Doodling a lot, doodling, but never kind of committed to it like I am now.”

Inspiring caricatures

He used to love MAD Magazine, especially Mort Drucker’s masterful caricatures of celebrities that appeared in the TV and movie parodies. Nealon was also an avid fan of Al Hirschfeld, “Broadway’s King of Caricature.”

“And I had two caricatures of my parents hanging on the wall in my bedroom,” he recalled. Those were drawn by a Parisian caricature artist, each framed separately and “were amazing.”

“I’ve never seen anything that great,” he said. “And every night I lay down, and I looked at those things, and I think subconsciously I was studying them and looking at how he exaggerated everything.”

When he started posting his caricatures on social media, he didn’t hear much in response from those inspiring the drawings.

“I never really heard back from anybody I sketched or did a painting of maybe because they didn’t follow me until recently,” Nealon said.

When he did start hearing from famous fans, the responses were mostly positive.

“(David) Letterman loved his, Brad Paisley loved his, the (Chris) Farley camp liked his …There’s just like one or two that were a little sensitive about it. And there was one where they said, ‘Under no terms can you use this photograph for promoting your book.’”

So how does Nealon go about creating a caricature?

First, he picks his character: “It could be someone who interests me or someone who has an interesting face or a great reference photo that I found,” he said.

A lot of his drawings are done on digital tablets, and he adds paint to the images later on. He very loosely outlines his character’s face, and exaggerates it. Next, he moves to the eyes.

“I like to get the eyes first because they’re kind of indicative of the rest of the face, because I do think you see the soul in people’s eyes,” he said. “And from there, I just try to pick the features that are the most outstanding. You know, that are a little exaggerated to begin with. And then I just push that and make them more exaggerated.”

There is a downside to creating caricatures though, and it’s that wherever Nealon goes, he feels like he’s walking past funhouse mirrors. He sees people’s exaggerated features, and they look like how he would draw them.

“And it’s a little scary,” he said.

Johnny Carson

Nealon is especially pleased with his Johnny Carson caricature because it reminds him of making his debut appearance on “The Tonight Show” — a moment that for him outshines other career highs.

“It was just such a dream come true for me. And then I got a panel with Johnny, which was a very rare thing for a comic on their first outing. So that was the highlight of my career to this day, more so than ‘Saturday Night Live’ or ‘Weeds’ or any Adam Sandler film or whatever I’ve done,” Nealon said.

He was extremely excited after he passed the audition, and it came time to do the show. He was standing behind the curtain and heard his introduction: “Would you welcome Kevin Nealon. Kevin,” he recalled Carson saying.

“I came out for a rousing round of applause, and Johnny Carson was over on my right with Ed McMahon,” Nealon said. “And as I was walking out to my mark on the shiny black floor, I forgot my act. I could not even think of my act. And I got to my spot and the audience is still applauding, and I’m still forgetting. And when the last clap ended, thank God I remembered my starting point.”

Chris Farley

Nealon’s caricature of the late, great Chris Farley is especially meaningful, as the two worked together on “SNL” for five years.

Nealon remembers Farley’s talent well, and also how much he desired being liked and getting the laughs.

(C) 2022 Kevin Nealon “He was always trying to be funny, and it was unfortunate that he couldn’t just relax and realize that he was enough on his own,” he said. “He didn’t have to constantly get approval. And also he was a train wreck. It wasn’t a surprise what happened to him. In fact, he wanted to be just like John Belushi because he’s from Chicago. And unfortunately, he did become just like Belushi. They both died at 33.”

Nealon said Farley was the only person who ever came close to making him break character on “SNL” during the famous Chippendales dancers sketch featuring Patrick Swayze.

“I never broke character in that show except this one time, I almost did. But I didn’t. Every time I looked up from the clipboard to see him dancing — the belly sloshing around and the stretch marks, I just had to keep looking down at my clipboard. It was so challenging to get through that sketch.”

Howard Stern

Nealon is a big Howard Stern fan, so it’s no surprise that his caricature of Stern is one of the most compelling in Nealon’s book.

Nealon said about eight years ago he decided to finally face his fears by allowing Stern to interview him.

“I noticed that Howard Stern’s interviewing technique changed over the years, and he seemed to be a little more relaxed and much more confident and secure in himself,” he said. “And so I went on there, and I was prepared for any kind of question. But he was very respectful, and we had a great interview, and we got laughs. And I was floating on cloud nine after that.”

But there was one question that Stern did ask Nealon that was similar to his earlier style of interviewing, in which he’d catch guests off guard by asking surprising and, at times, salacious questions. It was a question about Nealon dating fellow “SNL” cast member Jan Hooks.

“He asked me if I had ever gotten into Jan Hooks’ pants, and I said, ‘Yes, I did. And they were very, very tight on me.’”

-

The ongoing legacy of Nintendo's GoldenEye 007

In 1995, the James Bond franchise was reeling. The producers hadn’t made a movie in almost seven years, the biggest gap between any two Bond films. Their previous two entries — “License to Kill” and “The Living Daylights” — featuring Timothy Dalton as 007 had underwhelmed audiences and box offices alike. Furthermore, the Soviet Union had broken up, removing the villainous stakes of many of the movies.

MGM Studios reset the table. They hired Pierce Brosnan to replace Dalton as Bond and inserted Dame Judi Dench as the first female M, head of the M16 intelligence service. These changes were meant to reflect a more modern Bond and to provide commentary on how the character would evolve.

Additionally, MGM licensed the Bond rights for a videogame tie-in in hopes of boosting hype around the film. Japanese-based gaming giant, Nintendo, landed the rights and tasked one of their premiere game studios, Rare, to create it for their as yet unreleased console, the N64.

“(Rare) wanted to turn down Nintendo’s offer to give them the game and to develop it. They were afraid that it wouldn’t go very well because games made in response to movies or games that followed the plot of movies tended to be notoriously bad, and so they just didn’t want to bother with it,” Alyce Knorr said.

Knorr is the author of the Boss Fight Books entry “GoldenEye 007,” which outlines the shaky start, unlikely success and ultimate legacy of one of N64’s greatest videogames.

She told Wiconsin Public Radio’s “BETA” that Rare thought so little of the opportunity, they turned the game creation over to a group of unseasoned developers.

“They were underdogs, and nobody really expected much out of them. They were just sort of giving them a project to cut their teeth on, and it ended up being one of the greatest first-person shooters of all time,” Knorr said.

First-person shooter games or FPS had taken the PC gaming world by storm with games like Doom, but they were scarce on console gaming units like Nintendo, Sega and upstart Sony Playstation.

For project lead Martin Hollis, creating as real as a James Bond experience as possible for the player was priority number one.

“The game was sort of designed backwards in the sense that the team developed spaces and levels before they had developed objectives for the player to complete in those levels,” said Knorr. “So, what you had was a bunch of random hallways and rooms and certain levels that you didn’t really need to go down to get anything or do anything in the mission. But they were there just because it made the space feel more realistic.”

To achieve this, Hollis and his team were granted access to the movie set while it was shooting. They took hundreds of digital photos and scanned them into their software.

“They went as a team into the film studio. They walked around the sets,” said Knorr. “They sort of gawked at Pierce Brosnan walking through the canteen. So, they all got a kick out of that. And while they were on that trip to the studio, they took photos on a very early, very enormous digital camera, took those back to their studio campus at Rare and scanned them in. So, a lot of the textures in the game, like on the walls or the floor of the different level spaces, are literally photos from the film set.”

A bubbling worry during the development was the N64 console itself was behind schedule. The team didn’t actually know how it would function.

“When the team started developing the game, there was no N64 yet. So, for a lot of development, they had no idea what they were working toward in terms of the N64 hardware capabilities. They didn’t know what the controller would look like. They didn’t know how fast the graphics would run or how much storage space they would have for graphics. They were sort of just keeping getting updates from Nintendo on what aspirationally they were going to come up with, and then they adapted as they went,” Knorr said.

When Rare finally received the specs of the N64 and its capabilities, they were blown away by one certain concept, the new controller. Knorr said that this new controller — the first to feature an analog stick — would help the team reinvent console gaming.

“The control stick where you can move your character around completely in three-dimensional space was really revolutionary at the time when games like Super Mario 64 or Mario Kart 64 came out,” said Knorr.

“The GoldenEye development team was playing those games and saying, ‘Wow, this is amazing. We should make a fully three-dimensional game,’” Knorr continued. “They had originally intended for the game to be on the rails where you’re kind of directed through the game automatically. You don’t get to move around freely. But once they saw what the N64 was capable of and how fun it was to move a character through 3D space, they were inspired to take the game off the rails and allow players to move the character all around the level and explore and get lost and sneak up on people and all of those fun things we love about the game.”

Due to the many delays, GoldenEye 007 was released nearly two years behind schedule, just before the follow-up film to “GoldenEye,” “Tomorrow Never Dies.” Knorr said that at first, it was a “slow burn” in terms of public reaction given that Bond fandom had turned its attention to the new movie. She said a crafty marketing move with Blockbuster offering full refunds for unsatisfied customers helped people find GoldenEye 007’s secret sauce — its multiplayer mode.

“It had one of the highest rental rates of a game at the time. So, people were renting it, falling in love with it, seeing how fun it was, the multiplayer especially, and then going out and buying it,” Knorr said.

“So, it sold slowly and steadily and then it kind of caught on as a cult phenomenon. Everyone was playing at each other’s houses. It was a real social game… It really became a cult classic for playing on your couch with your buddies, with the pizza and just kind of having a hilarious good time.”

The irony of the game is that it became more popular than the movie. While Pierce Brosnan’s Bond got the franchise back on track, GoldenEye 007 made more money and has the longer legacy in pop culture, according to Knorr.

“If you talk to a lot of gamers from this era, they’ll tell you that they played the game before they ever saw the movie,” she said. “The legacy of the Goldeneye game is that it brought first-person shooter gaming to an entire generation of gamers who were playing games only on consoles at the time. And for that reason, I see Goldeneye as the direct ancestor of Call of Duty, Halo, Fortnite, all these first-person shooters today. I think they owe Goldeneye their popularity and their success in some way.”

Episode Credits

- Doug Gordon Host

- Adam Friedrich Producer

- Steve Gotcher Producer

- Steve Gotcher Technical Director

- George Saunders Guest

- Kevin Nealon Guest

- Alyse Knorr Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.