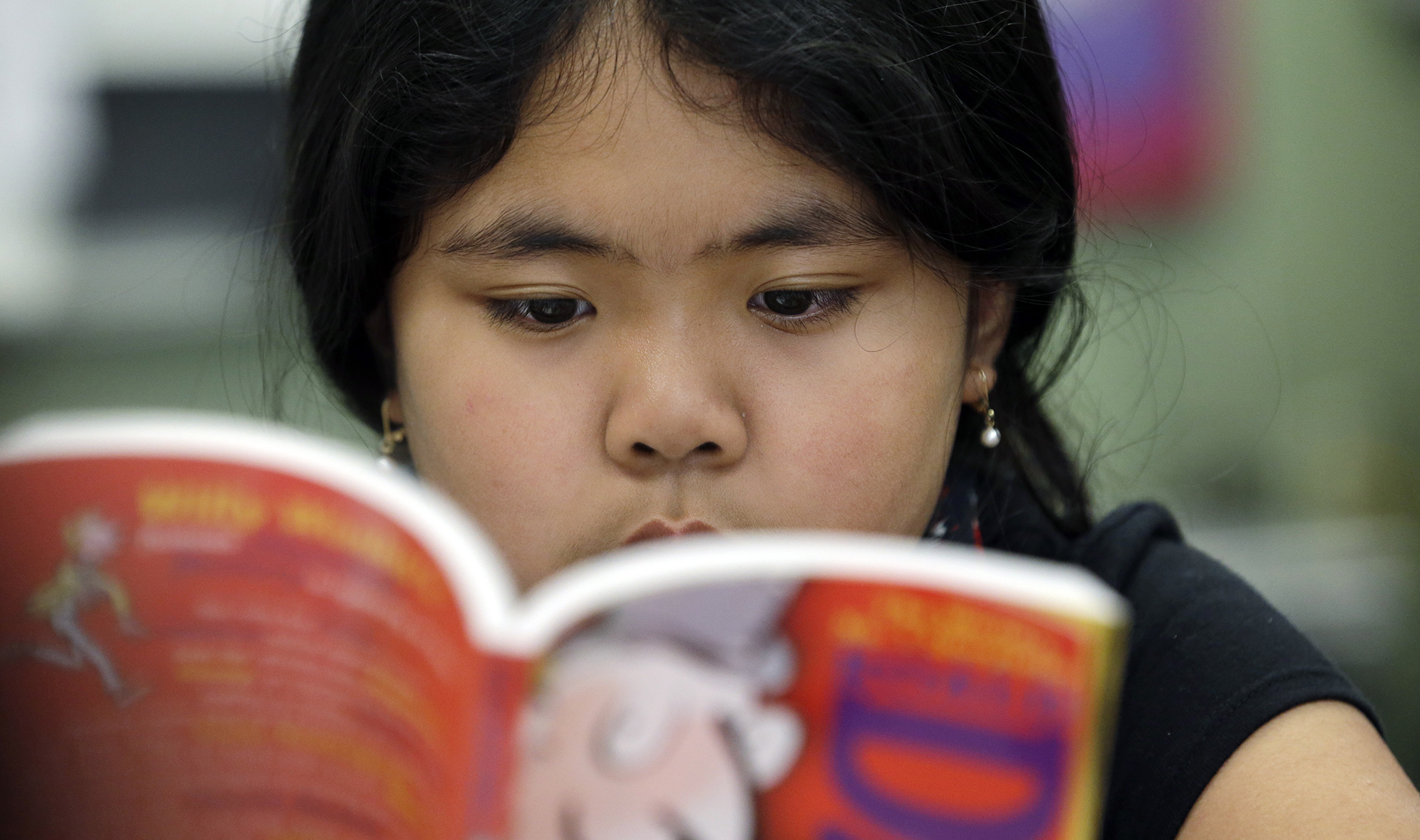

Five-year-old Naja Tunney’s home is filled with books. Sometimes, she’ll pull them from a bookshelf to read during meals. At bedtime, Naja reads to her 2-year-old sister, Hannah.

“I learn things that my brain will always know,” Naja said during an appointment at Group Health Cooperative’s Capitol Clinic in Madison.

Naja’s brain is in a critical phases of development, and it’s being stimulated by a home environment that prioritizes education.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

But children who don’t have this same experience early in life — especially those growing up in poverty — could experience delayed brain development that significantly harms their educational progress, according to recent research by psychology Professor Seth Pollak and economist Barbara Wolfe at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Their study shows a direct link between poverty, brain growth and gaps in test scores later in life.

“Now, we know that that achievement gap in poverty is at least partially explained by slower brain growth attributed to poverty,” said Pollak.

The study found that as much as 20 percent of the gap in test scores of low-income children is explained by developmental lags in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. These are the parts responsible for learning, including attention, emotion regulation, processing complex ideas, memory and comprehension.

“In many ways, children living in poverty had profiles that looked like children who were being maltreated, yet they were receiving very good care from their parents,” said Pollak.

Children living in households making below 150 percent of the federal poverty rate, or $36,000 for a family of four, were the most affected. An estimated 28 percent of Wisconsin’s children live below that level.

Pollack said he hopes to see his findings put into action with programs for children in early childhood.

“The more we understand about the mechanisms being affected by poverty, I think that makes it much more likely that we can take the resources, whatever resources we have and direct them to interventions that are really targeting the way poverty is affecting children’s growth,” he said.

One intervention program that’s been fairly successful is Reach Out and Read. The program gives books to children when they visit their doctor for checkups.

Francesca Vash is a nurse practitioner at the Group Health Cooperative Capitol Clinic in Madison, one of the 160 or so Reach Out And Read programs in the state. Her patients include children from families that don’t have much access to books.

“No matter the age of the child I always talk about the importance of reading and in a 4- or 5-year-old I may say why are these books important, you know, what’s good about reading? And we talk about how reading is good for your brain,” she said.

Ed Hubbard, a UW-Madison educational phsychologist, said Pollak’s study built on existing science and made new connections.

“We already knew about the impact of poverty on brains, we knew about the impact of poverty on education, but to actually put it all together I think was really critical to move the debate forward,” he said.

But, he said the growing body of evidence that early childhood poverty can affect achievement later in life means policymakers need to be doing more.

“We’re getting more and more strong evidence about this,” Hubbard said. “But I feel like the political will isn’t necessarily there.”

State legislators on both sides of the aisle are beginning to agree that more needs to be done to address early childhood. State Sen. Julie Lassa, D-Stevens Point, is part of the Legislative Children’s Caucus, which launched in April. She said Pollak’s research is the proof they needed to take action.

“To me there shouldn’t be any more arguing about the science,” she said. “So now that we have this research and evidence, what do we do to help tackle the problem?”

But, she said the caucus doesn’t have any specific plans to introduce legislation yet.