Waupun Correctional Institution inmate Cesar DeLeon said he has punched the wall until his fist is bloody during 15 years in prison in which he has rotated in and out of solitary confinement.

“I can’t understand why I have to do it,” said DeLeon, 34, “but the pain somehow gives me a sense of reality.”

DeLeon is in prison for armed robbery and kidnapping. He also is facing trial for attempted homicide for stabbing a Columbia Correctional Institution staff member in 2014 with scissors after he was denied a promotion at the prison library where he worked.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Brandon Christian said he fantasizes about the violence he will commit if he ever leaves solitary, where he has been for more than seven years. Once, allowed additional time out of his cell for good behavior, Christian attacked another inmate.

The interior of a solitary cell at the Wisconsin Secure Program Facility in Boscobel, Wis., seen during a media tour in 2001. Inmates may place the mattress on the floor which in turn creates a desk-like area for studies. Joseph W. Jackson III / Wisconsin State Journal

“Someone was talking crap about me and I didn’t know who so I just picked someone and stabbed him,” Christian, who is serving time at the Wisconsin Secure Program Facility in Boscobel, wrote in response to a survey by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

After two and a half years in isolation — spending at least 22 hours a day alone in a tiny, solid-walled cell — fellow Boscobel prisoner Ernesto Cervantes wrote in response to the survey that he is no longer capable of “normal human interaction.”

“I have not been able to function properly in a social setting,” Cervantes said of his experience after release from administrative confinement, a status with no specified end date. “I think others are talking about me and feel watched. I also feel like I have lost proper comprehension as when people are speaking to me it sounds like gibberish noise.”

These are some of the voices of Wisconsin prisoners kept in administrative confinement — a little-known category of solitary that the state Department of Corrections describes as “an involuntary non-punitive status” for inmates who pose “a serious threat to life, property, self, staff or other inmates, or to the security of the facility.”

The agency says these inmates are so dangerous that they must be confined for months, years — even decades — in a cell the size of a parking space with no human contact at least 22 hours a day.

State Department of Corrections officials denied reporters’ requests to interview inmates in person about their experiences in administrative confinement, so the Center mailed surveys to more than 100 who had been held in 2016.

The Center’s survey — conducted in the wake of an inmate hunger strike launched in June aimed at ending long-term solitary confinement in Wisconsin — asked about prisoners’ living conditions, mental health status, whether they received regular meals and whether they had committed or been a victim of violence while in administrative confinement. Several, including DeLeon, 34, participated in the hunger strike; some of them were force-fed.

Sixty-five inmates, many of whom have committed horrific crimes including multiple murders, violent attacks and sexual assault, responded to the surveys.

One respondent to the Center’s survey was in solitary for about 28 years; another has served 20 years.

The results of the survey were stark:

- Ten inmates reported attempting suicide while in administrative confinement. One said administrative confinement “makes you numb, violent, hateful, loud, disrespectful (and) suicidal.” Most described feelings of isolation, hopelessness, anxiety or paranoia.

- Of the 65 respondents, 26 claimed they have had medications or medical devices withheld or threatened to be withheld by security staff who distribute prescriptions or that they had overheard it happening to other inmates in solitary.

- More than a third of the respondents — 28 inmates — said they had been treated violently by other inmates or prison staff; 13 acknowledged harming or threatening to harm staff members or other inmates.

- Several described sleep deprivation from screaming and banging from other inmates and perpetual lighting.

- Thirteen inmates had food complaints, with some saying guards sometimes failed to deliver meals or that portions were inadequate, leaving them hungry.

How to manage such violent or non-compliant inmates — without worsening their behavior or mental health problems — is a big challenge for prison systems. Because of the negative effects of long-term indefinite solitary confinement, Colorado has largely ended this practice, which a top United Nations expert has said is equivalent to torture after 15 days.

In 2015, the Wisconsin Department of Corrections implemented policies — although not all inmates were aware of the changes — to reduce the amount of time inmates spend in solitary for disciplinary reasons and narrowed the types of offenses that can land them there. It also has made moves to remove prisoners with serious mental illnesses from solitary and to require that psychological staff provide input when such inmates are facing placement in solitary, spokesman Tristan Cook said.

The result is a large drop in inmates in all forms of solitary confinement from a high of 1,362 in March 2014 to 1,073 as of Feb. 28, Cook said. Of those, 93 were in administrative confinement.

“DOC has made significant reforms to the restrictive housing process with the goal of minimizing … (its) usage for all inmates and eliminating the use of restrictive housing for inmates with serious mental illnesses,” he wrote in an email.

As of Oct. 1, 2015, Wisconsin held about 3.7 percent of its inmates in solitary confinement for at least 22 hours a day, 15 continuous days or more, compared to a national average of about 4.9 percent, according to a study released in November by the Association of State Correctional Officials and Yale Law School. The practice has gone from “central to prisoner management” to one used “only when absolutely necessary and for only as long as absolutely required,” the report found.

There are signs that Wisconsin is attempting to improve conditions for inmates held in solitary. Gov. Scott Walker’s 2017-19 Department of Corrections budget request includes changes to solitary to boost mental health care and to allow some inmates with serious mental illnesses to spend up to 20 hours a week out of their cells for programming and recreation.

‘Prison within a prison’

Former Waupun prison psychologist Bradley Boivin said that the lack of an end date while in administrative confinement can be especially damaging to inmates’ mental health, creating a “prison within a prison.” The Center approached Boivin last year after inmates raised questions about why he had left DOC.

Former Waupun Correctional Institution prison psychologist Bradley Boivin is photographed on Sept. 8, 2016. Boivin left his job at the prison earlier in 2016 after he expressed strong disagreement with prison officials over several issues, including the treatment of inmates, especially those with mental illness.Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism

“Imagine being told you’re going to prison for five years or you’re going to prison for as long as we want to keep you there,” Boivin said. “The ambiguity of it creates additional levels of psychological distress for the inmates.”

Boivin said he resigned after trying unsuccessfully to make changes from within at Waupun.

“It wasn’t about correction at all,” he said. “It was about perpetual punitive behavior (towards the inmates). That’s what I couldn’t be a part of anymore, I guess.”

In solitary units, Boivin said, individuals with the highest mental health classifications are required to be seen by a psychologist once a week. Inmates with a classification of less severe mental illness are seen every two weeks. The brief sessions take place through the inmate’s cell door, allowing others to hear. Inmates call them “drive-bys.”

“There’s nothing clinical or therapeutic about (weekly check-ins) whatsoever. It’s really just a quick check-in,” Boivin said. “That’s it, they’ll say, ‘I’m fine,’ and you walk away.”

Suicide attempts, drugs withheld

In the surveys, most inmates presented bleak descriptions of life in solitary confinement.

“I’ve tried many times to hang myself with a sheet, overdose on medication. I start to see things or people who isn’t there; I talk to myself,” wrote Quenton Thompson, 35, who is serving a life sentence at the Boscobel prison for killing his pregnant girlfriend and her unborn child.

Shirell Watkins, 37, said he has tried twice to hang himself. Watkins, who is serving a 25-year sentence for reckless homicide, said he has spent years in various forms of solitary at three institutions, most recently Green Bay Correctional Institution.

He described “severe mental anguishment, depression, sleeplessness, high level of stress, constant self-communication, headaches, weight fluctuation, eye aches, hyper-reaction to situations/incidents, isolation/loneliness, short attention span, poor concentration and at times poor memory and difficulty concentrating.”

In early 2016, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported that one staff member was fired, one resigned and another retired from the DOC-run Milwaukee County Secure Detention Facility after they were caught on audiotape taunting an inmate and withholding his medication. He was being held in solitary confinement.

Thompson, the inmate at Wisconsin Secure Program Facility, said officers sometimes withhold medication from him “just to give me a hard time.”

Boivin used to hear these kinds of complaints from inmates, and he usually did not believe them. But the psychologist said he witnessed it himself at Waupun in 2015 after a sergeant, upset with an inmate, threatened to withhold his medication.

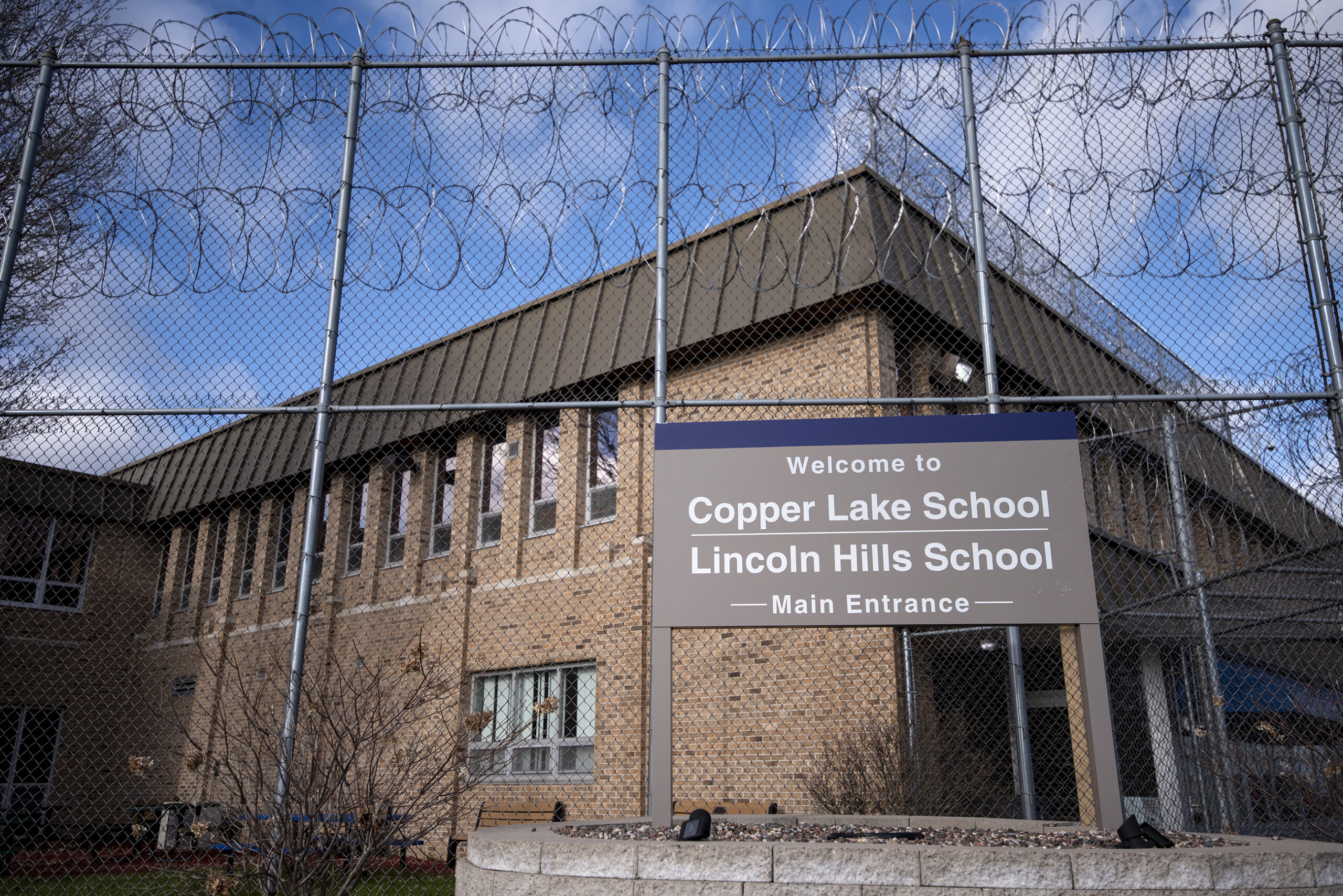

The problem, Boivin said, is that untrained non-medical staff should not be administering medicine. DOC has acknowledged the practice is “not acceptable,” requesting more than $1 million over two years for trained medical staff to administer medication at the embattled Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake juvenile prisons.

Cook did not answer questions about whether DOC is considering changes to how medicine is administered in the adult prisons.

Suicide watch ‘humiliating’ for inmates

In Wisconsin, some of the harshest treatment is reserved for inmates who want to kill themselves. Boivin said he personally and professionally felt these suicide watch placements were more torturous than solitary confinement itself.

An inmate in so-called observation status is confined in a cell with a hard bed with a thin rubber mat. The prisoner wears a paper security gown or a quilted security smock. The lights are on 24 hours a day, and, initially, he is not allowed any property, even a book.

In extreme cases, inmates are strapped down, restrained at their shoulders, their wrists, their ankles and their knees, in an “eight-point restraint.” Boivin said he has seen inmates restrained for hours or days, nude except for a washcloth covering their genitals.

“It’s humiliating, it’s degrading,” Boivin said. “They’re just kind of there, like a tied down animal.”

In 2015, there were 80 inmates with serious mental illnesses in solitary who had a total of 132 placements in suicide watch, according to a DOC budget request.

After a couple of days in observation, Boivin said, the “decompensation” is noticeable. Inmates’ eyes become bloodshot and watery, and they can become aggressive, delirious and eventually “shut down.”

Days filled with boredom and rage

Inmates were asked to describe a typical day in administrative confinement. Many wrote of repetitiveness, spending the entire day in bed or that the “days blur into one another.” Reading, watching TV, working out in their cells or the “rec cage,” and writing letters are some of the ways inmates keep busy.

Eric Conner, 30, is at Boscobel serving 30 years on his most recent sentence after stabbing another inmate and injuring a correctional officer. Cook said in all, Conner has had 56 conduct reports since he was imprisoned in 2008 for murder. During his time in solitary, Conner wrote that he hears his victim telling him to kill or harm himself. “I’m stuck in the cell and have nothing to distract me from him,” he wrote.

Christian, 29, said he has been in solitary confinement for more than seven years — including 3.5 years in administrative confinement — while serving a 29-year sentence at Wisconsin Secure Program Facility for first-degree sexual assault with a dangerous weapon and armed burglary.

“I pace my cell for hours thinking about all the horrible things I’ve done and the horrible things I will do,” Christian wrote, adding that he would have “no problem” assaulting an officer if given the chance.

Student Carley Waits, an intern with the University of Wisconsin-Madison PEOPLE program, contributed to this report. The Center’s reporting on criminal justice issues is supported by a grant from Vital Projects at Proteus. The nonprofit Center (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.