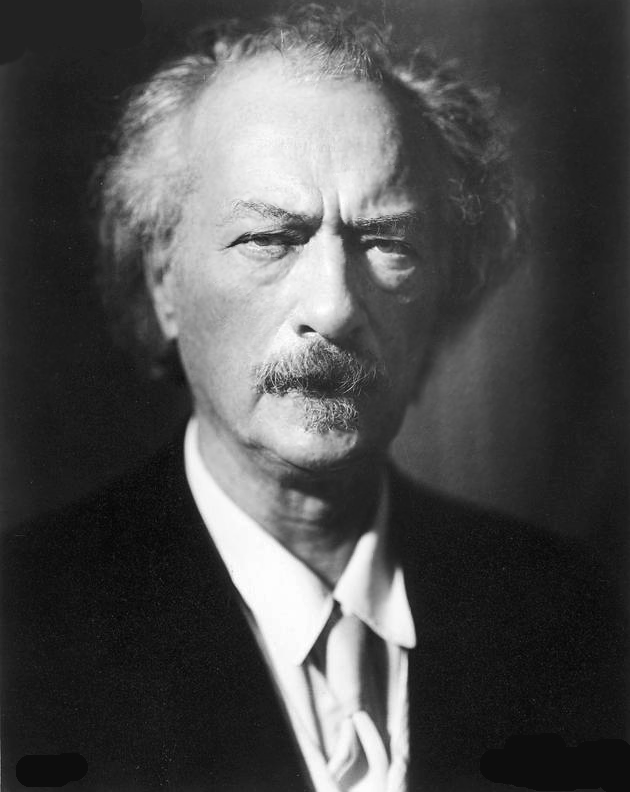

According to piano virtuoso Ignacy Jan Paderewski, in addition to stamina, dexterity, and an ear for music, a concert performer needs a good memory. During the early years of his career, he found out that memory can take more than one form.

In 1890, for a French colleague, Paderewski agreed on short notice to give a concert of French music. He agreed to play two concertos and a dozen short pieces–all of which he had to learn in the course of two weeks.

By the day of the concert he had learned all of the pieces and could play them all without a single mistake. But ten minutes before he was to perform, he began to doubt his memory.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“It was an agony!” he said years later. “I had to look at the music–the concertos especially–just before I went onto the platform.” The concert included established repertory and music by little-known contemporary composers, and he was still consulting the scores at the last minute.

He got through the program to the satisfaction of the audience and the composers who were attending, but three days later he found that he couldn’t remember a single piece.

“Not one!” he said in his memoirs. “It was gone.”

He came to the conclusion that a big effort of forced memory would achieve only temporary results. “I crammed and I stuffed myself literally like one of the famous Strasbourg geese!” he said, and warned students that reliable and enduring results in learning music are the product of “continuous daily efforts,” whereas the result of a single intense effort will be “absolutely sterile.”

A musician making a last-minute push to memorize a piece, he said, is like students that “enjoy themselves for a whole year until the time comes for the examination, then they make a supreme effort and acquire superficial, but brilliant knowledge for the moment.”

“Very soon,” he said, there’s “nothing left of it–nothing!”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.